Episode #85: Art Fact and Fiction: Did Michelangelo Paint the Sistine Ceiling Alone, on his Back? (S10E02)

In our tenth season, we’re going at art history with a skeptical eye and a myth-busting attitude to uncover the fictions and facts about some of our favorite artists. We’re starting our season today with this fascinating theory: did Michelangelo paint the Sistine Chapel Ceiling all alone, while lying on his back?

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts and FOLLOW on Spotify

Don’t forget to show your support for our show by purchasing ArtCurious swag from TeePublic!

SPONSORS:

Wondrium: Enjoy a free month with unlimited access

BetterHelp: Listeners enjoy 10% off your first month of counseling

Storyblocks: Get unlimited downloads at Storyblocks, a subscription-based provider of stock video and audio

Feals: Become a member and get 40% automatically taken off your first three months of premium CBD with free shipping

Want to advertise/sponsor our show?

We have partnered with AdvertiseCast to handle our advertising/sponsorship requests. They’re great to work with and will help you advertise on our show. Please email sales@advertisecast.com or click the link below to get started.

https://www.advertisecast.com/ArtCuriousPodcast

Episode Credits:

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Logo by Dave Rainey. Additional research and writing by Jessica Wollschleger.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits:

Music by Storyblocks. Ads: "Dakota" by Unheard Music Concepts is licensed under BY 4.0 (Betterhelp)

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Episode Transcript

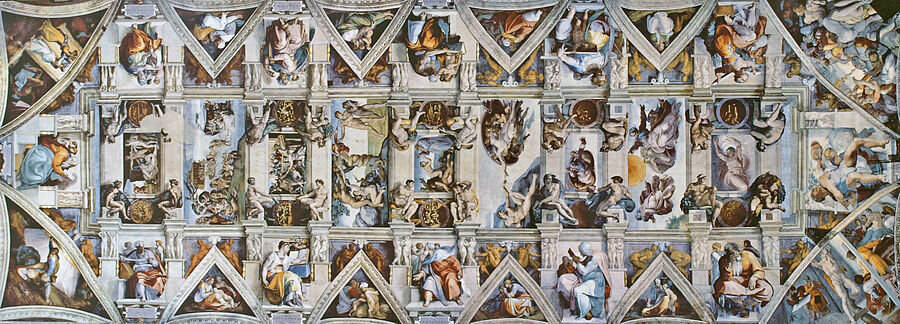

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, more outrageous, or more fun than you can imagine. Welcome to a new season, season 10, in which we’re going to dig deep on some great art historical facts--and fictions. In this episode, we’re getting into Michelangelo and the painting of the Sistine Chapel-- was it really as dramatic as it was made out to be, with Michelangelo toiling alone, on his back, for years straight? This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

I’ve been discussing the idea of the tortured artist for years now-- my second episode of this podcast, all about the death of Van Gogh, actually touched on this quite a bit, because we love thinking of artists as moody, temperamental, and solitary. And though Van Gogh, for me, will always seem to scratch that mythological itch best, the painter and sculptor Michelangelo Buonarroti feels like his Renaissance equivalent: a bit of a loner, prone to doing everything himself because he didn’t trust others, a perfectionist needed things to go his own way--so everyone else needed to back off.

This emotional profile of Michelangelo was established not long after the artist himself passed middle age, making it into the big time with exactly the project we’re discussing today--his painting of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling. Get those shot glasses ready, because it’s Vasari time! (I have this imaginary drinking game where I’m assuming that there’s at least one listener out there doing a shot every time I mention Giorgio Vasari, the big daddy of art historical biographies). So, according to Vasari, who was the first person to publish a biographical sketch of Michelangelo, the temperamental artist had such a rough start on the Sistine Ceiling that he threw a tantrum, locking the door to the chapel and refusing to let any of his assistants in to help him continue with the massive project. Another early biographer, Ascanio Condivi, claimed that the ceiling was painted, quote, “without any help whatever, not even someone to grind his colors for him.” Unquote. So both of Michelangelo’s biographers went big to make sure that he was seen as this singular, solitary master, and then this idea went even deeper into our cultural subconscious with the help of Irving Stone’s extremely popular biographical novel from 1961, The Agony and the Ecstasy, which was later made into an equally popular and award-nominated film in 1965, starring Charleton Heston as moody Michelangelo and Rex Harrison as moody Pope Julius II. (You’ll note that Irving Stone was also the man who wrote the biographical novel, Lust for Life, that also idealized Van Gogh as that perfectly tortured genius, so it’s interesting to think of how Stone single-handedly became a huge mythmaker for the art world). But are these visions actually accurate? Was grumpy Michelangelo condemned to work alone, lying on his back, with paint and sweat dripping into his eyes into the late hours of every night?

To understand the facts and fictions of this oft-told tale, we first should discuss the Sistine Chapel itself to get a sense of the scale of Michelangelo’s commission for the ceiling. The Sistine, as we currently know it, was built by the decree of Pope Sixtus IV--who was in fact Pope Julius II’s uncle--and Sixtus, by the way, is where we get the name “Sistine”. Sixtus wanted a new chapel built on the site where an earlier, smaller chapel had once stood, hoping to build a larger and more useful space that could function as a center for prayer and for official church business, like its famed use as the location of the papal conclave for the choosing of a new pope.

Sixtus hired the Florentine military architect Baccio Pontelli in 1477 to begin construction on a design meant to exactly match the (actually kinda funky) dimensions reported in the Old Testament as those of the Temple of Solomon in ancient Jerusalem, meaning that the finished chapel is twice as long as it is high, and three times long as it is wide. It was, and is, a stunning building with a lot of wall space, as you can imagine, so after the building was completed in 1483, many of Italy’s most sought-after Renaissance artists were commissioned to paint frescoes featuring scenes from the life of Christ on one of its long sides, and the life of Moses on the other. A bunch of big names worked to beautify Sixtus’s new chapel: Pietro Perugino, the leader of the fresco project; Sandro Botticelli; Cosimo Rosseli; Luca Signorelli; Piero di Cosimo; and Domenico Ghirlandaio, who would eventually go on to train none other than Michelangelo in his studio. With that roster of creators, you can imagine that the frescoes on the walls of the Sistine Chapel are awesome-- and they truly are. The ceiling, though, was… fine. Standard, actually. It was produced with a simple design of a starry night sky, though this one was produced as lushly as possible with the use of expensive ultramarine pigments and gold leaf. But still: a starry sky, a rather calm envisioning of the heavens above. And who knows-- maybe that would have done the job handsomely and we’d just be here, talking about Perugino’s frescoes, except that the ceiling began cracking around 30 years later. Rome, you see, is kinda like Washington D.C. in that the city was built upon some swampy terrain, and the literal shifting ground beneath the Sistine led to some structural issues. Though the building was sturdily built and was able to survive the strain, the ceiling itself, held up by these shifting walls, wasn’t quite so lucky. Large cracks began to splinter across the vault, and though the ceiling itself was bolstered, repaired, and plastered over, the appearance obviously suffered, with the previously blue-and-gold heavens marred by a large white scar.

In 1504, Julius II was elected Pope, and as we have discussed in a past episode of ArtCurious-- that’s episode #33 about the rivalry between Michelangelo and Raphael, if you want to go back and listen--one of his goals was to arrange for a number of major building and renovation projects across the Vatican and across Rome, including the complete overhaul of St. Peter’s Basilica, the epicenter of the Roman Catholic church. He campaigned to beautify and aggrandize Rome, and thus, himself-- this guy had vision, no bones about it. And as part of that vision, he wanted to be sure he was commissioning the most stunning works of art--painting, sculpture, and architecture, that the world had yet seen. So working with the land’s tip-top artists, as his uncle, Sixtus IV, had done, was key to making it happen.

Julius’s connection to Michelangelo began with a commission for the pope’s epic tomb, a monument to be filled with life-size statues created out of expensive Carrara marble. Michelangelo’s connection to sculpture was a lifelong one, a connection he claimed as part of his self-mythologizing. According to the artist in discussions with Vasari, his childhood wet nurse, who also served as his nanny, was descended from a long line of stone carvers, and it was from her family, he said, that his interest in sculpture grew. As he noted to Vasari, quote, “Along with the milk of my nurse I received the knack of handling chisel and hammer, with which I make my figures.” Unquote. And it is indeed via sculpture that Michelangelo became famous, having been celebrated far and wide by 1504 as the preternaturally talented maker of the Vatican Pietà and of his statue of David in the city of Florence, Michelangelo’s hometown. So when Julius came calling, summoning Michelangelo for the prestigious tomb commission, he was thrilled, and he got to work designing a magnificent, imposing structure for Julius’s final resting place, which ultimately would have included 40 life-size figures over which he toiled for nearly a year. But if you listened to episode #33, then you already know that this tomb project didn’t exactly go as planned. Michelangelo did eventually create a much smaller, hugely scaled-down version of the tomb almost half a century later, and much with the help of his assistants, but the grand project it was supposed to be… it was not. And part of that was that Julius opted to stop the tomb project and diverted funds to the massive redesign of St. Peter’s, as well as to fund several small-scale wars he fought to reclaim power over several papal states. And Michelangelo was maaaaaaad. He had spent all this time toiling, planning, and shipping marble back and forth from Cararra on his own dime--er, florin-- and he was devastated at having the commission pulled out from under him. So upset was he that, for practically the rest of his life, he referred to this project as the so-called “tragedy of the tomb.” He left Rome, returned to Florence, and intended never to return. But Julius had other plans, and was unwilling to let Michelangelo go. Though he didn’t want to move full-speed ahead with the tomb project anymore, he did have a few other ideas in mind, and Michelangelo was grudgingly lured back. After yet another failed project under Julius’s purview--this time for an 11-foot-tall bronze sculpture of the pope to be placed in the city of Bologna, another fascinating story for another episode of ArtCurious-- Michelangelo, always a testy sort, was rightfully grouchy about working for the pope, but it was the pope. What could he do, say no to one of the most powerful patrons in Europe? He needed to work. He needed commissions, because commissions brought money, and money was a good thing to have for, you know, living and stuff. And in 1508, the pope came with another commission--which was less of a request and more like an official order: I want you, Michelangelo, Julius said, to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Coming up next: we’re digging deep into fresco alongside Michelangelo and his helpers. Stay with us, after a quick word from our sponsors--and remember, by purchasing from our sponsors you not only grab a good deal for yourself, but you help keep us afloat. Thanks for listening.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

Famously, Michelangelo balked at this commission. Sculpture was in his heart and in his blood, and he just didn’t feel like he was a very good painter, let alone someone well-versed in the notoriously tricky medium of the fresco. Michelangelo didn’t want to take the job, but when the pope tells you to jump, you’ve gotta ask, “how high?” So he signed the contract and gave into the fact that he now had several intense years of work ahead of him, and to manage it, he had to put together a solid team of assistants to help him bring it all together. Assistants. Michelangelo needed assistants. Get ready for a deep dive into fresco, because it’s worth a little sidebar here to confirm just how treacherous it can be to pull off--just ask Leonardo da Vinci about that one and how it worked out for his Last Supper, and hint hint, by the way, for a future episode of this season of the podcast.

Alright. On to fresco, sometimes referred to as buon fresco, or “true” fresco. To make a fresco involves painting on a very thin layer of wet plaster, typically called by the Italian term of “intonaco.” As the intonaco dries, a chemical reaction takes place that locks in any pigment placed onto it, essentially hardening into the surface of the wall or ceiling being decorated. Fresco was especially popular Southern Europe during the Renaissance (as well as long before and long after) because it was not only cheap and made with easily available materials--lime derived from limestone, and sand mixed with water-- but the region’s dry, hot weather during the summertime meant that plaster could dry fast, and thus, frescoes could be made quickly. But that same quality also meant that it had to be made quickly, with artists painting into the intonaco fast before the intonaco dried, because once it dried, it was done. And if it didn’t look good, you’d have to chip it all off and start the whole process over. Fresco, you see, is not for the faint of heart, and you’ve gotta be prepared to pull it off. So an artist needed to make sure to have their cartoons--meaning their preparatory drawings or sketches, not the Saturday morning animation--ready to go for each day’s specific work, called the “giornata,” from the Italian word for “day.” Upon the beginning of the work day, a fresh patch of intonaco would be laid, and the cartoon would be placed atop it, where it could be traced by a knife, stylus, or another tool to scratch the outline of the design into the plaster. Sometimes another method, called “pouncing,” would be used, where the artist or an assistant would poke tiny holes along the outlines of figures or items in a cartoon and then would dab at the holes with a small, porous bag of charcoal dust, which would leave little dots that could be connected to form the design on the plaster. And then the painting, the adding of the color, would be added. Consider, though, that paint didn’t come in tubes, or pots or buckets, at this point--the whole “paint in tubes thing,” by the way, was one of the revolutions that brought forth the Impressionists, a revolution in itself. Paints at this point needed to be made by the artist and/or their assistants from a variety of ground plants and minerals, like saffron, cinnabar, lapus lazuli, and malachite. No easy feat in and of itself, the preparing of paints alone was a huge and truly important job. So between the planning, the drawing, the mixing and grinding of pigments, the chiseling, the transferring of cartoons, the actual fresco painting, and dealing with any errors or mistakes, you can imagine that lots of people needed to be a part of a fresco project, especially one as gigantic as the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, measuring about 131 feet long by 43 feet wide, or the equivalent of more than 5,000 square feet.

Is it any surprise, then, that not terribly long after Michelangelo signed the contract for the commission, he immediately jumped to securing help? According to surviving documents and by Vasari’s accounts, Michelangelo put his oldest friend, a fellow artist named Francesco Granacci, in charge of recruiting a team of assistants. Granacci and Michelangelo had met while both were apprenticing in the workshop of Ghirlandaio, himself a Sistine Chapel artist famed for his works in fresco, and who subsequently taught both boys the tricky trade, though neither Michelangelo nor Granacci went on to become professional fresco artists themselves. Granacci mainly painted banners and backdrops for theater performances, but, according to Vasari, he was loyal and humble, a, quote, “merry fellow,” whom Michelangelo could trust and whom, conversely, could deal with Michelangelo’s mercurial spirits. By October 1508, Granacci had assembled the whole team, which included four experienced Florentine fresco artists named Bastiano da Sangallo, Giuliano Bugiardini, Agnolo di Donnino, and Jacopo del Tedesco. Joining them was a plasterer, Pietro Rosselli, who was tasked with chiseling away that original, damaged star-spangled ceiling, and rounding out the group was another sculptor, Pietro Urbano, who had previously worked with Michelangelo in Bologna. Cloistered away in Michelangelo’s small, rather spartan studio, these eight men prepared themselves for the monumental task of completely remaking the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. But before they did that, they needed to determine how to even reach the ceiling in the first place.

The vaulted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel soars about 68 feet off of the ground, or the equivalent of a six-and-a-half story building. Obviously it required some kind of scaffold, but the scaffold needed to be created in a way that wouldn’t affect the chapel’s usage as a place of prayer and religious services-- that was one of Julius’s non-negotiables, that the chapel continued to be in use even while it was renovated. So Julius asked Donato Bramante, the architect, to design scaffolding that would reach the ceiling but keep the floor of the chapel open. And Bramante delivered, but his design stipulated that the scaffolding would basically be a set of platforms suspended from ropes anchored into the ceiling, meaning that holes would have to be drilled into Michelangelo’s work surface to support the platforms. No, no, no, Michelangelo said. That won’t do. So he took it into his own hands--Michelangelo, it would turn out, would be an accomplished architect himself, by the way--and he designed a scaffolding system that functioned like interconnected bridges anchored near the Chapel’s arched windows and braced against the walls, leaving the ceiling free of any holes or markings. It covered about half the chapel, and thus only required moving halfway through the project, which was a huge time-saver (you can see Michelangelo’s brief sketches for this scaffolding, as well as an artist’s rendition of it from a virtual reality simulation of the Sistine Chapel by Epic Games, included in the blog post for today’s episode). And most fascinatingly--and here’s where we bust another Michelangelo myth-- the bridge-like platforms were designed to be held approximately 7 feet below the ceiling, meaning that Michelangelo and his assistants would be able to stand, craning their necks upward and with their arms raised over their heads, to complete that day’s giornata. Just below the platform, Michelangelo’s assistants suspended large canvas sheets so that drops of paint and chunks of chiseled plaster would be caught, thereby protecting church officials congregating in the chapel at any given time--and provided Michelangelo with privacy (and thus avoiding the prying eyes of Raphael, Bramante, the Pope, any many others).

Next, Team Sistine gets down to business. And there’s a learning curve to that business. Come right back.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

The actual beginning of the fresco project was a bit rocky, to say the least. Michelangelo and his team began painting the ceiling on the east end of the chapel, near the entrance, painting a scene of the Biblical great flood from the Book of Genesis. Not terribly long after completion, a portion of the panel grew moldy because their plaster mixture was off and contained too much water, an error purportedly discovered by the assistant Giuliano Bugiardini. So off came the moldy part of that panel, chipped away, and with the fresco begun anew, a process that totaled almost three months of lost work, according to some estimates. Though this was a regrettable sidestep, it does allow us as art historians, both professional and amateur, a little hint at Michelangelo’s team at work, because comparisons of the painted figures has yielded a theory that only two figures--an old man carrying a younger one, often thought to be a father supporting his dead or dying son-- were actually painted by Michelangelo himself. The others, most historians agree, were completed by the artist’s assistants.

But any good storyteller knows that a plot about a struggling artist toiling all by his lonesome is such a good dramatic hook, way more than a plot swirling around a stable artist working in tandem with his teammates. And as we have mentioned time and again on ArtCurious, Giorgio Vasari often liked to spice up his stories for the reader's interest. In his recounting of the moldy flood panel, Vasari writes that Michelangelo had a fit, locking the doors to the Sistine and refusing to let his assistants back in, opting instead to finish the chapel project all by himself. But this appears to be Vasari engaging in early myth-making about Michelangelo, who was reportedly one of his idols. Vasari’s story, while making Michelangelo out to be a bit of a tyrant (which may have been true), also makes the artist seem that much more magical, a super-human figure opting to toil alone to complete an almost impossible project. It’s a romantic thought, so much more interesting. But it’s not true. We do know that Jacopo del Tedesco left Rome in January 1509--but whether he quit, was fired, or left for another reason is up for debate, but it is clear that it wasn’t a happy parting, as he apparently grumbled about Michelangelo all over town upon his return to Florence--but he was quickly replaced by another assistant, a man named Jacopo Torni.

The point about Jacopo del Tedesco’s departure is an important one because it presents what would eventually become a pattern with the Sistine project. For whatever reason, by the end of 1509, nearly all of Michelangelo’s original group of assistants had dispersed, leaving Michelangelo to lament in a letter to his brother that he, quote, “had no friends of any sort.” Unquote. Michelangelo was nothing if not a bit prickly-- and certainly super exacting about his wants and requirements-- so it’s not impossible to imagine that the assistants may have grown tired of him and the grueling fresco scheme, but here’s the important thing: if assistants left, they were replaced with new helpers. After Bastiano da Sangallo, Giuliano Bugiardini, and Agnolo di Donnino exited the picture, they were replaced by Giovanni Trignoli and Bernardino Zacchetti, fresco painters from Reggio nell’Emilia in Northern Italy. And not everyone left, mind you: Pietro Urbano, Michelangelo’s sculptor pal, stayed on for the duration of the project.

A final point about Michelangelo and his assistants: remember that at the very beginning of the Sistine Chapel commission, Michelangelo wasn’t thrilled about the project because he essentially felt like he was neither a good painter, nor someone skilled in fresco. When, after more than two years, the first half of the chapel ceiling was revealed to the general public, his efforts were met with incredible praise. Michelangelo’s biographer, Ascanio Condivi, wrote that, quote, “The opinion and expectation which everyone had of Michelangelo brought all of Rome to see this thing... this new and wonderful manner of painting.” Unquote. In short: Michelangelo and his team killed it. And knowing that people were digging what he was doing was a major boon to the artist’s fragile ego. He grew more confident; and at the same time, he became far more comfortable with his fresco technique, because working on something for hours upon end for literal years will surely make you an expert really quickly-- it’s like Malcolm Gladwell’s”10,000 hours” rule, which theorizes that you need to spend that many hours practicing something before you can master it. Michelangelo may not have quite reached 10,000 hours of working time by late 1510 or early 1511, but there’s no doubting that he not only became more skillful, but also a faster worker. The learning curve was long past, and Michelangelo and his assistants were able to complete the remaining frescoes on the ceiling of the Chapel by the fall of 1512, which was described as Vasari as, quote, “such to make everyone astonished and dumb.” Unquote. The Sistine Ceiling was a hit, and though it was a bit of a slog at certain points, the great Michelangelo never toiled lonely and abandoned, lying flat on his back.

We’ve separated fact from fiction in Michelangelo’s story today, but we’re still left with one question: where does the myth of Michelangelo’s great suffering in the name of the Sistine project come from? Interestingly, it partially stems from Michelangelo himself. In 1509, he included a sonnet in a letter to his friend Giovanni de Pistoia, which presented a litany of ailments produced from his work in the Sistine. In translation, it reads, quote:

I've already grown a goiter from this torture,

hunched up here like a cat in Lombardy

(or anywhere else where the stagnant water's poison).

My stomach's squashed under my chin, my beard's

pointing at heaven, my brain's crushed in a casket,

my breast twists like a harpy's. My brush,

above me all the time, dribbles paint

so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!

My haunches are grinding into my guts,

my poor ass strains to work as a counterweight,

every gesture I make is blind and aimless.

My skin hangs loose below me, my spine's

all knotted from folding over itself.

I'm bent taut as a Syrian bow.

Because I'm stuck like this, my thoughts

are crazy, perfidious tripe:

anyone shoots badly through a crooked blowpipe.

My painting is dead.

Defend it for me, Giovanni, protect my honor.

I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.

Best of all is the metaphorical cherry atop this sundae: a little sketched self-portrait, presenting the artist standing, his head tipped awkwardly back and his arm straining upward to paint a delightfully cartoonish figure (the Saturday morning version, this time around), hilariously chubby and donning spiky hair. Michelangelo himself busts this myth about himself, presenting a picture of the artist standing while at work. It surely wasn’t a comfortable experience, and be fair, he seems to have liked presenting himself as a miserable wretch, but this wretch absolutely worked with others to bring his incredible artwork--a history-making one at that--to fruition.

Coming up next time on ArtCurious, we’re returning to one of the most lauded and popular artists of the 20th century, and one of the most popular female artists of all time. Are her paintings actually risque interpretations of female anatomy? We’re separating fact and fiction this season, and this one is a theory that just won’t quit. That episode is coming up in two weeks. Don’t miss it.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal. HUGE thanks to Jessica Wollschleger for her awesome research and writing help with this episode. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, and our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com. Our podcast services are provided by our friends at Kaboonki. Subscribe now to their new show, Subgenre, a podcast about the movies, hosted by Josh Dasal, and visit subgenrepodcast.com for more details. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator, which means you can donate tax-free to ArtCurious to show your support. To find the donation links and for more details about our show,, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod. And we have podcast merchandise! Check out the link to our TeePublic store in the show notes on this episode, or on our website.

Check back with us soon as we explore the facts, and the fictions, of the unexpected, slightly odd, and strangely wonderful in art history.