Episode #84: Art Fact and Fiction: Is "Mona Lisa" Really Leonardo in Drag? (S10E01)

In our tenth season, we’re going at art history with a skeptical eye and a myth-busting attitude to uncover the fictions and facts about some of our favorite artists. We’re starting our season today with this fascinating theory: Is the Mona Lisa really just a portrait of Leonardo da Vinci in drag?

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts and FOLLOW on Spotify

Don’t forget to show your support for our show by purchasing ArtCurious swag from TeePublic!

SPONSORS:

Wondrium: Enjoy a free month with unlimited access

Indeed: Listeners get a free $75 credit to upgrade your job post

BetterHelp: Listeners enjoy 10% off your first month of counseling

Storyblocks: Get unlimited downloads at Storyblocks, a subscription-based provider of stock video and audio

Want to advertise/sponsor our show?

We have partnered with AdvertiseCast to handle our advertising/sponsorship requests. They’re great to work with and will help you advertise on our show. Please email sales@advertisecast.com or click the link below to get started.

https://www.advertisecast.com/ArtCuriousPodcast

Episode Credits:

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Logo by Dave Rainey. Additional research and writing by Mary Manfredi.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits:

Episode music by Storyblocks. Ads: "Dakota" by Unheard Music Concepts is licensed under BY 4.0 (Betterhelp); "Gourd Hunting" by Jesse Spillane is licensed under BY 4.0 (Storyblocks)

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Links and Further Resources

ABC News, Is Da Vinci's Mona Lisa a Self-Portrait?

The Atlantic, The Man Who Wants to Dig Up the Mona Lisa

BBC News Hour, Mona Lisa Identified?

Lillian F. Schwartz, “The Hidden Mona Lisa” (Video)

New York Times, It’s Time to Take Down the Mona Lisa

NBC News, Did Leonardo Paint Himself as the Mona Lisa

Perez Hilton, Is Mona Lisa a Drag Queen?

University of Heidelberg, Mona Lisa Heidelberg Discovery Confirms Identity

LaFarge, Antoinette. "The Bearded Lady and the Shaven Man: Mona Lisa, Meet" Mona/Leo"." Leonardo 29, no. 5 (1996): 379-83. Accessed May 10, 2021. doi:10.2307/1576403.

Pascal Cotte, Mona Lisa’s Spolvero Revealed

Episode Transcript

Okay, let’s rewind just a little bit in time. Not a few hundred years ago, not even fifty years ago, but only back about a decade. Let’s get back to the year 2010, which feels like a few hundred years ago at this point. The iPad was brand new. Lady Gaga wore the meat dress. Those godforsaken Vera Bradley bags were everywhere (sorry, y’all, but those were never my bag). and hey, guess what? There was a pandemic! Do you remember the swine flu? So, 2010 was a lot. But I’m not here today just to take a trip down memory lane. I bring 2010 up because in that year, there was a very interesting art historical request. That year, members of Italy's National Committee for Cultural Heritage petitioned the French government to allow them access to a chapel in western France long considered the resting place of a long-dead Renaissance Master.

The Committee asked for permission to subject the purported remains of said Renaissance master to both carbon dating and DNA profiling, as well as digital anatomical reconstructions to answer a bunch of questions: do the remains really belong to one of the most innovating and imaginative artists in history? What secrets of this artists’s work have been buried with him? And, most curiously, what did this artist really look like?

It’s not a question that most of us really think about too much-- what a historical figure’s face looked like, specifically. But a leading group of Italian scientists and historians really wanted to get as much information as they could, because they truly, fascinatingly, wanted to know: what did Leonardo da Vinci really look like? And is his most iconic work of art, the Mona Lisa, actually a portrait of the artist in drag?

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, more outrageous, or more fun than you can imagine. Welcome to a new season, season 10, in which we’re going to dig deep on some great art historical facts--and fictions. In our season opener, we’re talking Leonardo, self-portraiture, self-identification, the true identity of Mona Lisa and this: is it a portrait of Leonardo himself? This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

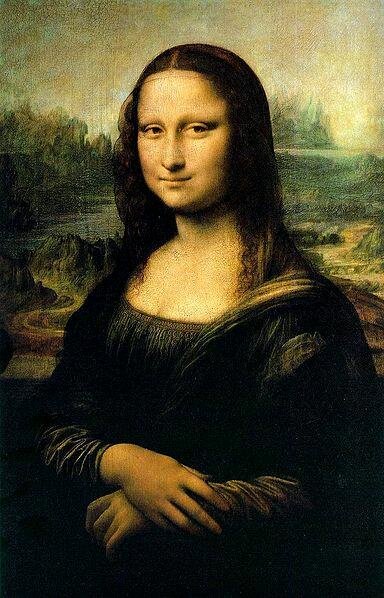

You know that the Mona Lisa, arguably the world’s most famous single work of art, is a big one for ArtCurious, since Mona was the subject of our very first episode ever, an episode that has been a listener favorite and that inspired an even deeper dive in my recent book, also named ArtCurious. But as I’ve discussed previously, as famous as Mona is, it’s really hard to enjoy the painting itself if you have the pleasure--or even displeasure, some think-- of viewing her in person at the Louvre in Paris. It’s all barriers, bulletproof glass, guards, and -- when not in a pandemic--hordes of visitors pushing and prodding to get to the front row to get as close a look as possible. It’s no surprise, then, that questions arise about the work--and the identity of Mona herself--when you can’t even get a good look at her. And her status as the most iconic, and perhaps most instantly identifiable painting ever, means that people sometimes lob extra meaning or mystery onto her. What’s so great about this painting? Who’s this woman, and why do we make such a huge deal about her? And indeed, acquaintances have asked me about Mona Lisa, wanting to know the “real” scoop about this portrait of a not-traditionally-attractive woman that almost single-handedly draws millions of visitors to the Louvre each year. Surely, these acquaintances have pressed, surely there’s something going on behind this painting, something that explains why it’s such a world-famous piece. And I understand why these questions bubble up. For a work to be this lauded, this iconic, it’s gotta be more than a portrait of a renaissance woman… right?

Back in the very first episode of ArtCurious, I gave you the background on Leonardo himself as well as the generally -accepted theories surrounding the creation of this work, but I’m happy to give you a bit of a refresher here. Most art historians believe that Leonardo da Vinci began this portrait around 1503 or 1504, but that he never officially finished it, and indeed, he appears to have worked on it on and off for the better part of two decades, tweaking brushstrokes here, changing an element there. He took it with him when he moved to France under the purview of King Francis I. And it was Francis who purchased the work from an assistant of Leonardo, after the master’s death in 1519. And that’s why this work by an Italian artist has called France her home for nearly half a millennium, as it carried on through the French monarchy, through Napoleon’s reign, and as one of the attractions at the Louvre after that royal palace was officially converted into a museum.

One of the reasons that Mona is such a big draw is the acclaim that arose over her theft in 1911, which we’ve discussed in depth. But here’s another reason why she’s a big deal, though it’s probably not a reason that pops to the front of mind for the average Louvre attendee. But it is a fact: there actually aren’t all that many surviving works by Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo, that intensely curious polymath, an inventor, poet, astronomer, architect, engineer, proto-paleontologist, etc. etc. etc. was a painter, true, and yet it was just one of his many talents and interests. I often say that the term “Renaissance Man,” meaning someone with a broad and/or intense knowledge and skill base, was basically invented to describe Leonardo. But there was a flip side to his undying curiosity. He was a procrastinator extraordinaire, putting a project--like the Mona Lisa--aside to work on something else, perhaps something totally different, like plans for diverting the Arno River in Florence, or conceiving of a redesign of the cathedral in Milan. He had his hand in everything and that’s what he liked-- he liked, it seems, to begin projects. But carrying them to fruition was much harder, so he’d stop working on something when a new, and potentially more exciting, idea arose. Spread thin, serving many different patrons as well as his own busy mind, Leonardo was just slammed. He didn’t have enough time to churn out an incredible number of paintings. He also worked slowly and methodically, as a perfectionist is sometimes wont to do. There’s also his experimentation to consider. Leonardo merged his scientific and artistic minds frequently by trying new things, especially new materials and techniques, with occasionally disastrous results--as we discussed in our “Little Curious” episode detailing his lost painting of the Battle of Anghiari in Florence.

And this combination of perfectionism, experimentation, and procrastination--as well as the passage of time-- means that there are less than two dozen surviving paintings by one of the most famous artists of the Renaissance. And of those two dozen, probably about half are generally accepted as being by Leonardo himself, other than a follower or imitator. So, yeah: any Leonardo painting is a big deal. But it would be a lie to say that any of Leonardo’s paintings is as big a deal as Mona is.

Mona’s part in Leonardo’s artistic output is herself in rarefied company as one of the few surviving portraits attributed to the artist. Most of Leonardo’s surviving paintings are religious in nature, which makes sense, as commissions in a highly Catholic country. But Leonardo surely subsidized his livelihood with commissioned portraits, too, and that’s where Mona Lisa comes in. And while other works are super-widely thought to be portraits completed by Leonardo, like his gorgeous Lady with an Ermine from around 1489, and the portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, from around 1474 or so, those and other portraits have been a bit controversial in the past, though they are basically widely accepted as Leonardos now. But that level of controversy has never haunted Mona. She’s always been a Leonardo. What’s controversial about her, though, is who Mona really is. And we’ll get into that controversy right after this quick break. Stay with us, grab some cool deals and coupons, and support our show.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

When I typically talk about the Mona Lisa, I have a pat answer about her identity. When I was a budding art historian in college and beyond, I was told that we know the details of the woman we call Mona Lisa. A real woman, named Lisa Gherardini, is the sitter in this picture. Gherardini was the wife of a very wealthy Florentine silk merchant, named Francesco del Giocondo, who purportedly commissioned the artist to paint his wife’s portrait. And there’s not an insubstantial amount of evidence to back this up, beginning first with the title of the painting. Mona Lisa. Mona is a contraction of the Italian word for “lady, or my lady, “ Madonna-- which was then abbreviated down to “Mona”-- kind of the way we say “ma’am” in English, instead of the more formal sounding “madam.” And yeah, the lady’s name was Lisa. My Lady Lisa: Mona Lisa. Need more convincing? If you go to the Louvre, you’ll see her noted additionally as La Joconde, which is the French translation of the phrase La Gioconda, or the Gioconda woman-- the wife, then, of Francesco del Giocondo. (The Louvre, by the way, totally stands by this identification, with the wall label reading Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo, called La Joconde or Mona Lisa.

We actually know a little bit about the potential commissioning of this work, because we have some historical documentation of it. First up--get your drinks ready-- it’s Giorgio Vasari, that semi-credible rascal who’s the granddaddy of artist biographers. Vasari noted in his bio of Leo that, quote, "Leonardo undertook to paint, for Francesco del Giocondo, the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife." Unquote. And one of Leonardo’s assistants, a man known by the name of Salai, had a painting called “La Gioconda” listed as part of his estate after his 1524 death, which he inherited after Leonardo’s death five years prior.

So, there you have it. That’s the backstory of the Mona Lisa. It seems pretty watertight to me. But for a not-insignificant portrait of the art world, there’s always the question. Is this exact painting the one really known as “Mona Lisa?” Or was it another painting? One that exists in limbo today as one of those “maybe Leonardos,” or a lost work entirely? Maybe this painting has been misidentified all these years ago? So who would the sitter in this portrait be, if not Lisa Gherardini? I’ve read many of them: she’s Isabella of Aragon, the duchess of Milan; she’s an even more famous Isabella-- Isabella d’Este, the marquise of Mantua and a hugely important figure in both art and cultural history of Europe, who does have another unfinished chalk-and-pastel portrait by Leonardo to her name, also in the Louvre. Some say she’s the same woman as in Leonardo’s Lady with an Ermine, a noblewoman named Cecilia Gallerani. It’s even been posited that Mona is based on the appearance of one of Leonardo’s assistants and supposed lover. But. But but but. One theory has captured our collective imaginings because it’s so different. Subversive even. Mona Lisa, some have posited, is a portrait of Leonardo himself.

Okay, are you surprised that it has taken me this long to bring up the name “Dan Brown?” For those of you who are too young to have known the phenomenon of The Da Vinci Code, or perhaps have mercifully forgotten-- no judgment, though, I totally blew through it back in 2003, too--just know that it was a thriller by American author Dan Brown that involved a chase for the fabled Holy Grail and involved a lot of riddles and clues pertaining to art history, especially, as you may surmise from the title, the works of Leonardo da Vinci. And I’ll just put a little hint of my own out there that this won’t be the last time we’re talking about either Leonardo or Dan Brown in this season of the podcast. But part of the enduring interest in Dan Brown’s book--and in its association with the Renaissance master-- is that Leonardo himself was fascinated by the workings of the human mind. Jason Rosenfeld, a professor of of art history at Marymount Manhattan College, argues, quote, “[Leonardo] is interested in symbols, he is interested in puzzles, he is interested in keeping things kind of hidden, and this idea about the picture sort of relates to that, that is part of this whole mythologizing of Leonardo as someone who is playing tricks, who is always a step ahead of a viewer, and someone who is making you think of his works in a very different way.” Unquote. At gatherings Leonardo would devise riddles, which he called “prophecies,” which he would share with the various courts he served; it’s Leonardo as entertainer, and several of his “prophecies” still exist--like this one: Quite, “Serpents of great length will be seen at a great height in the air, fighting with birds.” unquote. Leonardo wrote the answer right next to it. It’s, quote, “of snakes, carried by storks.” Unquote. I never said that it translates well to a modern audience, but there you go. Leonardo was witty, a bit of a prankster, and he liked jokes. All of this makes some wonder: what’s cleverer than obscuring your own identity and making everyone think that you actually painted a woman instead of yourself?

What do we want to make of this idea of Leonardo-as-prankster, doing a gender performance as “Mona Lisa,” whoever that is? We’ll get into it when we come back from this short break.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

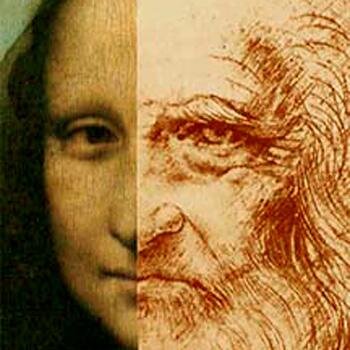

It’s entirely possible that this idea--that a jokester Leonardo disguised himself as a sallow, eyebrow-less lady and painted his own portrait-- had been floating around for a while, but it really caught fire beginning in 2010 with the publication of Leonardo’s Hidden Face, a book co-written by artist Lillian F. Schwartz, writer Renzo Manetti, and art critic and Leonardo scholar Alessandro Vessozi. In this book, the authors posited the idea based on Lillian Schwartz and own modelings of Mona Lisa, something that had intrigued her for decades. In 1984, she scaled and bisected a (purported) Leonardo self-portrait called Portrait of a Man in Red Chalk and juxtaposed it next to the Mona Lisa. This combined image shows similarities between the eyes, forehead, nose, and mouths of the figures in both works. Thirty years later, with the combined use of computer programs, x-rays, anatomical analysis, the authors have updated Schwartz’s original lo-fi experiment and found compelling similarities between the known Leonardo self-portrait drawing and Mona--most intriguing, that the figures appear to have the same supra-orbital ridge (or eyebrow ridge), associated anatomically most frequently with men. I know, I know. It’s not super convincing to me, but it has been convincing to others. The team behind Mona Lisa’s hidden face want to make it clear, though, that it’s entirely possible that Mona began as a true portrait-- though not of Lisa Gherardini, they say, but Isabella of Aragon, and then opted to fuse his own facial features with the original image. To be fair, this wouldn’t exactly be revolutionary, because artists use and re-use canvases, panels, even paper, all the time. And some scientists, like Pascal Cotte, have indeed uncovered some interesting underdrawings--including, perhaps, another face-- on the panel that was uncovered using multi-spectral analysis, as was reported last year in the Journal of Cultural Heritage. But whether or not that face belongs to Leonardo’s is still up for grabs.

All of this brings us back to the story at the top of the episode. 2010, the same year that Leonardo’s Hidden Face was published, that group of Italian scientists and historians petitioned to open the supposed grave of Leonardo, located in a chapel at the Chateau d’Amboise in France’s Loire Valley. And one of the reasons to open the grave was to explore the bones interred there and reconstruct the artist’s face to see if it matches up in any way with Mona Lisa. It seems far-fetched, but this team of Italian scientists performed a similar reconstruction in 2009, when they came up with a computerized model of the face of the great poet Dante Alighieri, again based on cranial mapping. But with Leonardo, it has proved trickier, since he was buried in another country. And from most of my research, it doesn’t exactly look like permission to exhume the supposed Leonardo remains was granted. Whoever is buried at Amboise is still buried there, though it must be noted that a little plaque nearby writes that it is indeed the purported--not 100% confirmed--remains of the artist. It doesn’t appear that Leonardo has been exhumed quite yet, but people are still out there working on it.

Who has been exhumed, though, is, potentially, someone with a link to Lisa Gherardini. In 2013, another team of researchers opened the family tomb of the Giocondo family with hopes of identifying not Lisa Gherardini herself, but her son. The hope was to use her son’s DNA to match up with Lisa Gherardini’s supposed remains, which had been found in a Florentine convent where Lisa had died in 1542. After that, the scientists hoped to do similar cranial mapping to create a visualization of Lisa’s face that would then be compared to the Mona Lisa. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out, as the supposed remains of Lisa Gherardini were deemed too degraded to perform any DNA testing. And to make matters worse, it was discovered that no skull was located in Gherardini’s tomb, which ultimately ruled out all hopes of facial reconstruction. So the final verification of the true identity of Mona Lisa still remains.

Overall, though, Mona-who she really is, if she is really anyone at all or an amalgam or a symbol, or a portrayal of the artist himself, is just one of many, many mysteries surrounding this work of art. It’s an important piece, a famous piece, so everybody has a thought about it. Alessandro Vezzosi, one of the authors of Leonardo’s Hidden Face, revealed as much when he noted that the Mona Lisa is, quote, “like a mirror: Everybody starts from his own hypothesis or obsession and tries to find it there.” And it’s not hard to do, when your work of art is over 500 years old and there are gaps in its provenance and no 100% confirmation of the sitter’s identity from Leonardo himself. But I’ve mentioned it before and I’ll mention it again: it is a bit strange that Leonardo kept this painting with him for his whole life. If it was indeed a commission, it’s odd that it wouldn’t have ended up with the commissioning party. If it did come from Lisa Gherardini and the Giocondo family--which I still think is the likeliest case--why did Leonardo hold onto it for so long? Did the Giocondo family reject it? Was Leonardo so unhappy that he kept tinkering with it for his own purposes? Suddenly, things make just a tiny bit more sense if we think Leonardo kept it because it bore his own portrait. That jokester in disguise, hiding in plain sight. And to be fair, some have referenced that the surname “Giocondo” is actually an adjective, meaning jocular, joyous, carefree in Italian. Leonardo was known to make visual and grammatical puns--his Ginevra de ‘ Benci a prime example, with Ginevra bearing a resemblance to the Italian word ginepro, so Leonardo’s portrait showcases her flanked with its greenery. No one, perhaps, was more jocund than Leonardo himself. So perhaps, he really was La Gioconda in this case. As always, I’m skeptical, but one thing truly makes sense to me: I think I’ve got a good idea now why Mona Lisa has that incredible enigmatic smile. She’s amused, perhaps, after half a millennium, we’re still trying to figure who she truly is.

Coming up next time on ArtCurious, it’s another big big name of the Renaissance, known to be a surly, do-it-yourself type. But did he really do one of his biggest projects all by himself? We’re separating fact and fiction this season, and this episode is coming up in two weeks. Don’t miss it.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal. Huge thanks to Mary Manfredi for her awesome research and writing help with this episode. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, and our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com. Our podcast services are provided by our friends at Kaboonki. Subscribe now to their new show, Subgenre, a podcast about the movies, hosted by Josh Dasal, and visit subgenrepodcast.com for more details. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator, which means you can donate tax-free to ArtCurious to show your support. To find the donation links and for more details about our show, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod. And we have podcast merchandise! Check out the link to our TeePublic store in the show notes on this episode, or on our website.

Check back with us soon as we explore the facts, and the fictions, of the unexpected, slightly odd, and strangely wonderful in art history.