Episode #30: Art and Remembrance (Season 2, Episode 10)

It's interesting that literature seems to have cornered the market on artistic depictions of those who experienced the Holocaust firsthand. We think of The Diary of Anne Frank or Elie Wiesel’s Night first and foremost when we think of how war has been creatively represented by those who survived it-- or didn’t survive it. But it turns out that there were many artists who made visual representations of their experiences, too-- and lots of these individuals were prisoners, like Anne eventually became, in concentration camps.

// Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts!

Episode Credits

Additional writing and research by Patricia Gomez. Production and Editing by Kaboonki Creative. Theme music by Alex Davis. Research assistance by Stephanie Pryor. Social media assistance by Emily Crockett.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits

"Bittersweet" by Podington Bear is licensed under BY-NC 3.0; "Petite pièce minime No 2 - Batifol" by Circus Marcus is licensed under BY-NC 3.0; "Dreams Are For Living" by Daniel Birch is licensed under BY 4.0; "Galamus" by Circus Marcus is licensed under BY-NC 3.0; "Parting" by Alex Mason & the Minor Emotion is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "daedalus" by Kai Engel is licensed under BY 4.0; "Thistle Blossom Blue" by Axletree is licensed under BY 4.0; Ad music: "Off to Osaka" by Kevin MacLeod is licensed under BY 3.0

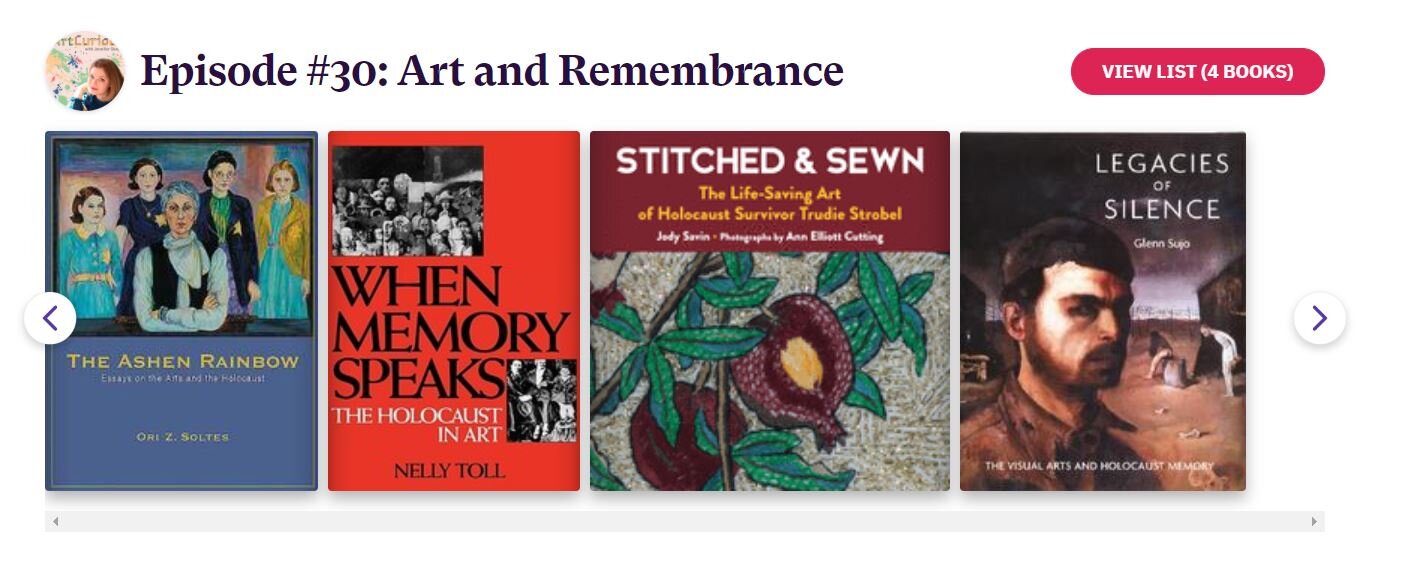

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Links and Further Resources

BBC: 'Haunting' art by Jewish children in WW2 concentration camp

CNN: Auschwitz's Forbidden Art

New York Times: ‘Art From the Holocaust’: The Beauty and Brutality in Forbidden Works

Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center

United States Holocaust Museum: Nazi Concentration Camps introduction

University of South Florida: A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust, Art of the Ghettos & Camps

Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum: Works of Art

Remember.org: Paintings by Jan Komski

Episode Transcript

Today's episode is brought to you by audible - get a FREE audiobook download and 30 day free trial at www.audibletrial.com/artcurious. Over 180,000 titles to choose from for your iPhone, Android, Kindle or mp3 player. Listen up and support our show!

There was nothing like World War Two, in terms of vastness of scope and the darkness of the times. Sure, there were other wars before-- including The Great War, World War I-- and there have been other wars since. And there will be other wars to come. But in terms of the abject horror that was spread throughout the world-- nothing has yet come close to World War Two-- not in reach or number of casualties. One witness to the war understood this and put her thoughts to paper, writing, quote, “I see the world being slowly transformed into a wilderness; I hear the approaching thunder that, one day, will destroy us too. I feel the suffering of millions.” Unquote. But this writer didn’t stop there- and in a beautiful turn of positivity, she continued by saying, quote, “And yet, when I look up at the sky, I somehow feel that everything will change for the better, that this cruelty too shall end, that peace and tranquility will return once more.” Unquote. This stunning statement was written by a 13-year-old Jewish girl hidden away in an attic in Amsterdam who would famously proclaim that in spite of everything, she still believed that people were essentially good at heart. This was Anne Frank, and her diary, written in the face of utter persecution during the height of World War II, has gone on to be translated into countless languages and has become a staple of school syllabi. Indeed, The Diary of Anne Frank is the quintessential primary source from World War II. And it’s not surprising to see why, given its remarkable insights considering the author’s young age and her situation. And it’s made an even more important record of the war because of the tragic reality that Anne Frank died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on March 12, 1945. Anne Frank was a witness and a victim of the worst war in history and of the Holocaust-- and her words, alongside those like Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi-- are among the best works of nonfiction literature to tackle the most terrible experiences of this war.

I find it interesting, though, that it is literature that seems to have cornered the market on artistic depictions of those who experienced the Holocaust firsthand. We think of The Diary of Anne Frank or Elie Wiesel’s Night first and foremost when we think of how war has been creatively represented by those who survived it-- or didn’t survive it. But it turns out that there were many artists who made visual representations of their experiences, too-- and lots of these individuals were prisoners, like Anne eventually became, in concentration camps.

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those can be paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, crazier, or more fun than you can imagine. And today, we’re shedding light upon the visual art created in the midst of the Holocaust as a way to document, to remember, and to rise above the horrors of war. Welcome to the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

In the past few episodes of the ArtCurious Podcast, there have been multiple periods in which we’ve discussed the trying circumstances in which some artists found themselves creating work-- the one that most vividly comes to mind for me is the U.S. combat artists of World War Two, who literally created sketches in war zones based on what they experienced firsthand. But those are artists who either enlisted in the armed services specifically to work, or were recruited-- again, on a voluntary basis-- to do so. But in terms of the works that were made during the Holocaust itself, it is really hard to imagine any artists creating anything at all.

Not that creating art in times of strife was a new endeavor by any means. As we mentioned in the first episode of this season, art and war have been linked almost from the beginning of time. As long as there has been conflict, there have been representations of conflict. The French Revolution, for example, kept going year after bloody year, and people kept painting. Even today, in an America still struggling with discrimination, censorship, and hate crimes, there are easy and widely available channels for artists-- especially minorities-- to create work in response to their experiences. But actively working as an artist-- or at least even attempting to produce art-- while you are struggling dearly for your own life? That’s exceptional.

What I find most interesting is not only the fact that there were incredible artists working during the Holocaust, but also that there are large troves of visual art that were produced in concentration camps-- a surprise, really, given not only the circumstances but also material limitations. So the big question, then, is this: why have we heard only dribs and drabs about these artists and their artworks? It’s a big question, and probably not one that we are going to fully answer today, but there are probably a few different factors at work here. The first is that many of those who produced art while being held in concentration camps are, at least to most of us, not famous artists, so they don’t have that big name-recognition factor that frequently grabs our attention. Then, there’s also just the fact that, in parsing through the remains of a war that ended only 70 years, it’s entirely possible that historians are still attempting to process the material. But if I were to pinpoint one single fact as to why we don’t hear a little more about these works, it’s this: they are hard to face. Think about some of the subjects we’ve already discussed this season: The Monuments Men, the Ghost Army, and the Fuhrermuseum. From our perspective, these all have happy endings-- the Monuments Men saved priceless cultural property from destruction and worked towards their return; the Ghost Army used their creativity to fool the enemy; and the Fuhrermuseum never came to pass. These have those wonderful Hollywood-ready stories that make us feel warm and fuzzy inside. But Holocaust artworks? They do the opposite-- they are a harsh visual reminder of the atrocities that human beings inflict on each other.

Before we step into the concentration camps, we need a little background as to who was creating work there. The first thing that many of us think about when we consider who was chosen by the Nazis to be shipped off to camps is those whose religious or political beliefs pinpointed them as so-called “enemies of the state.” We think of the millions of Germans and Austrian Jews, predominantly-- or at least I do-- but it wasn’t only them: it was also communists, the mentally ill, Roma, Catholics, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and homosexuals, as just a few examples. And included among these enemies of the state were thousands of artists and other creatives-- simply because the art that they created was not in line with the official supported state art of Nazi Germany. These artists-- whose works were called “degenerate”-- were mostly working in a very modern fashion, meaning that they prized things like abstraction, non-naturalistic colors, or simply creating art for art’s sake. And for many Nazi officials-- and certainly for Hitler and Göring-- that was just not okay. Not only was this art deemed too elitist or incomprehensible for the quote-unquote “good” German citizen, but it was considered suspect-- it did nothing to further the Nazi cause or agenda of pure Germanness, and couldn’t be appropriately harnessed for propagandistic purposes. And thus, it should be eliminated. A great purging of degenerate works of arts followed, beginning in 1933 following Adolf Hitler’s rise to power-- art that didn’t conform to that ideal of German purity were confiscated and destroyed. And what wasn’t destroyed were kept and used as examples of what NOT to do. In 1937, Adolf Ziegler, one of Hitler’s personal favorite painters, was tasked with putting together an exhibition of 650 of most offensive works of art confiscated during the previous four years. This exhibition, which traveled throughout Germany and Austria, is known simply as “The Degenerate Art Exhibition,” and included works by an incredible amount of famous artists, most of them German: Georg Grosz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Kurt Schwitters and others. Some non-German artists made the cut, too, and so Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky were also deemed the worst of the worst.

But purging these degenerate works of art would only eliminate part of the problem, Nazi officials said. That would only get rid of the troublesome works of art that had already been created. So, to avoid the possibility of NEW paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints coming to the forefront to challenge Hitler’s regime, it was necessary to purge artists as well. And this is how artists throughout Germany and German-occupied Europe were systematically selected and sent away. But just because these artists were captured and relegated to concentration camps doesn’t mean that they necessarily stopped practicing as artists.

In 2016, the German Historical Museum in Berlin opened “Art From the Holocaust,” an exhibition of 100 works that were clandestinely created by 50 Holocaust-era artists. Of the artists selected for the show, half were killed by Adolf Hitler’s troops, but their creations survived. And what was most exciting about this show is that, in many cases, it dispelled expectations about what art from the Holocaust could or should look like. To this point, curator Eliad Moreh-Rosenberg noted that when you say “exhibition about art from concentration camps, visitors quote “immediately think about stereotypical images from the Holocaust: barbed wire, yellow stars, chimneys.” And while those symbols still hold serious significance and are a huge part of our visual vocabulary when it comes to describing what the Holocaust looked like, that is not all there was-- art created by Holocaust victims and survivors was so much more than that. And that’s also where things get a little bit complicated.

First of all, some artists were specifically sent to concentration camps for forced labor-- but instead of the grueling forced manual labor of quarrying stones or working in factories, these artists were forced to create works of art for use by the enemy. On orders from the SS, prisoners assigned to offices and workshops made instructional drawings, models and visualizations of various initiatives, from plans for expanding concentration camps to providing visual records of prisoner health and the medical experiments performed on them. Some SS officers even exploited these quote-unquote “hired” artists for their own private purposes. According to the Auschwitz Museum and Memorial’s website, evidence remains that some artists were forced to produce everything from portraits to greeting cards or small craft objects, most of which were sent home to the officers’ family and friends. But this was probably the very best-case scenario, when it came to creating art within the concentration camps. You created-- but you were forced to do so. It was your job. Far more dangerous, though, were works of art created in secret. How and why that was done is coming up next, right after the break.

Do you want to help support this show? Not only can you donate to us on our website, but you can also benefit from a special offer. For listeners of this show, Audible is offering a free audiobook download with a free 30-day trial to give you the opportunity to check out their awesome service. Two books that are currently fascinating me are Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order) by Bridget Quinn, and The Art of Rivalry: Four Friendships, Betrayals, and Breakthroughs in Modern Art by Sebastian Smee. You can find these, as well as the biggest bestsellers like Turtles All The Way Down by John Green, or What Happened by Hillary Rodham Clinton-- and thousands more. And for every free trial, the ArtCurious Podcast gets a little kickback-- which is so incredibly appreciated. To download your free audiobook today go to audibletrial.com/artcurious. Again, that's audibletrial.com/artcurious for your free audiobook.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

Like nearly everything one could do in the camps-- of one’s own accord, that is-- art-making was grounds for punishment, and even death. In fact, several prisoner-artists lost their lives upon the discovery of their secret artwork by camp officials. And yet, art was made. In fact, some contend that it had to be. Indeed, curator Moreh-Rosenberg of the German Historical Museum makes this clear in her talks about the art from the Holocaust, saying, quote, “When you’re fighting for your life and your basic human needs, creating art is not just an escape, it’s an active choice of defiance.” Unquote. Decrees against artmaking in these camps were nothing if not explicit, and so making nearly anything could be seen as a violation of the authority of guards-- and the Nazi regime as a whole. And on top of all that, it was also illegal for prisoners to use any materials from SS officers for their own personal use, so to produce art from anything that wasn’t purposefully given to a prisoner would be a double assault. So prisoner-artists were very careful to push their boundaries just far enough, forcing themselves to be contented with whatever was already at their disposal, such as scraps of paper or crusts of bread. Frequently they’d repurpose objects already on hand-- old letters or book pages for drawing paper, or toothbrushes or broken chair legs morphed into standalone sculptures. But having a finished piece was only half of a problem that the artists faced, of course-- the other half was the need to conceal it. A frequent method of hiding works of art-- or indeed, anything of value-- in concentration camps was to bury the object with the hopes that a prisoner could return at a later date to retrieve it. But imagine the difficulty that this would hold-- not only in the possibility of being discovered by prison guards while burying or salvaging the piece, but also whether or not one’s memory could be accurately relied upon to help the prisoner find the work after months, or years, of hiding it away (and with one’s mind possibly unraveling in the meantime due to famine and hardship). And then there’s the environmental element. If you’re trying to bury a drawing, you’d better wrap it in something waterproof and aim to come back for it fast-- or else, it could just disintegrate. But through an intricate system of secret inmate communications and smuggling, some were lucky enough to conceal their creations-- and others were even luckier, escaping not just with their works of art, but also with their lives.

One of the most prolific artists held briefly at Auschwitz was Polish artist and political prisoner Franciszek Jaźwiecki. Jaźwiecki frequently made portraits of fellow prisoners-- hundreds of them in total, during his three years in captivity. These portraits, to me, toe some strange line between being cartoonish and lifelike, and upon first glance, I found them unsettling-- I still do. And it took me a while to determine why: it’s all in the eyes. They are shifted away, darkened, saddened. An art historian from the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Agnieszka Sieradzka, confirmed this in a 2015 interview with CNN where she said that the eyes of the prisoners that Jaźwiecki drew exude a, quote, “very strange helplessness.” Which, naturally, makes quite a lot of sense when you consider where and when these portraits were made. But, as Sieradzka further asserts, the need for prisoners to have an image-- any image-- of themselves during this immensely terrible time was so strong that they’d do almost anything to secure it.

The most interesting part of Franciszek Jaźwiecki’s drawings are that he seems to have taken them very seriously as historical documents- because he meticulously copied every prisoner’s serial number-- a five digit number of identification that was sewn onto each man, woman, and child’s jumpsuit. And Jaźwiecki recorded them all- and then hid each drawing, mostly on his own person, in his clothes, or in his bedsheets. Jaźwiecki was transferred to two additional concentration camps after Auschwitz and ended up in Buchenwald only weeks before American troops liberated him and 21,000 other prisoners in April of 1945. And when Jaźwiecki walked out of Buchenwald, he did so with hundreds of his drawings in his possession. He died of tuberculosis only one year later, and upon his death, his family donated his works to what would become the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. And remember those serial numbers that he documented in each portrait? This is the incredible part-- they have allowed historians to match these images of prisoners with prison logs kept by the SS and thereby identify and match names with faces.

While those like Franciszek Jaźwiecki created works of art that could function as records of a prisoner’s life and experience, others created simply as a way to hold onto their own humanity. The trauma of being starved, overworked, forcibly separated from one’s family and home, and constantly surrounded by death is, to put it ridiculously lightly, difficult for both the psyche and body to handle. And the Nazis did everything in their power to dehumanize their already broken prisoners, forcing them to shave their heads, to be stripped of their clothing and valuables, of anything that could personalize a person-- essentially breaking everyone down to identical masks of agony. But to write, sing, dance, or create a painting-- to create anything at all-- is like an extension of one’s self, and thus a reminder of who a person was before he or she was cruelly subjected to abject horrors. Art, for many became a reason for living when there was nothing left.

Another category of artists needs to be considered when we are talking about concentration camps-- and that’s to acknowledge those for whom art was simply a distraction or a coping mechanism-- a way to pass the time in an unending monotony of despair and sickness, or as a simple escape from harsh reality. One of the best examples of this motivation is also one of the most heartbreaking-- the simple and beautiful artworks created by children imprisoned during the Holocaust. In the Theresienstadt camp in what was Czechoslovakia during WWII, about 140,000 Jews were incarcerated, of which 15,000 were children. And to be fair, Theresienstadt was a kind of hybrid camp-- originally a transit settlement or assembly camp before being transitioned into a full-blown concentration camp. This means that there was access in this camp to some things-- like pencils and watercolors-- that were not readily available elsewhere. Not that this meant that life was dandy for the children of Theresienstadt. The reality is that, according to camp records, approximately 90 percent of children perished there. Parents, who might or might not have been cognizant of the terrible odds facing their children, naturally did whatever they could to protect them. According to Brian Devlin, a curator at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, families, quote, “tried to shield their children from the horror of their situation by occupying their free time with games, education and painting.” Unquote. This reaction should certainly sound familiar to anyone who has seen the 1997 film Life is Beautiful. And indeed, some parents encouraged their children to remember-- to harken back to times that were happier and simpler, and as a way to preserve what little hope could remain. A painting by a young artist named Ruth Cechova, who died at the age of 13, is a prime example of this. Cechova illustrates two identically-dressed girls, red-skirted and laying down on a blanket, sunbathing in a field of colorful flowers and shafts of wheat. Other images survive that show children playing games or celebrating special events or holidays-- birthdays, passover-- with their families. The downside was that when some of these drawings were discovered by camp officials at Theresienstadt, they were confiscated-- not as examples of dangerous defiance, but as proof that life at this and other concentration camps was sunny, peaceful, and joyous. No no no, it isn’t as bad as you’ve heard, the Nazis seem to be proclaiming with these images. Essentially, children’s personal drawings were reinterpreted and re-presented as Nazi propaganda.

Of course not every work of art that the Theresienstadt children created was this cheery and nostalgic. The vast majority of it wasn’t-- even if, on first glance, it seems to be. One drawing by Malvina Lowova, herself killed at twelve years old, is full of a swirling energy and color of a Cy Twombly painting. At the left of the scene is a golden sun peeking out from behind jade green hills and topped by a rainbow. But the subject matter of the scene below is actually rather grim. It illustrates the forced evacuation of Lowova and her family from their farm by armed Nazi soldiers, who threaten them with pitchforks-- a faceless mass of terror. In one single drawing, illusions of childhood innocence are shattered.

Just because World War Two ended in 1945 didn’t mean that art by and about Holocaust experiences petered out. In fact, after the war there was an influx of works from those who survived the Holocaust and lived to create art about it. One example of this is the work of Jan Komski, a Polish Catholic who escaped Auschwitz only to be arrested and sent to additional camps until he ended up in Dachau. Komski would survive to be liberated there in April 1945, and after his liberation, he moved to the United States, where he became an illustrator, working predominantly for the Washington Post. But it wasn’t just stories for the Post that he would go on to document, but also his own terrible memories of the horrors that the SS committed to him and his fellow prisoners. In one painting, Komski recalls a typical daily roll call, with an imposing SS official studying names on a clipboard while his associate points to the mass of identical prisoners clad in gray lined up behind him in silent hopelessness. In front of those prisoners, though? Piles of corpses collected on the ground-- those who didn’t live to see the light of this new day. Another painting, titled Hanging and Eating, presents viewers with a gruesome sight of a hanged man, bloodied and blindfolded, dangling from the gallows. But the worst part isn’t the hanged corpse-- it's the dozen or so prisoners surrounding him with their backs to the gallows, dressed in their striped jumpsuits and consuming their meager rations. They had grown so used to the death and violence that surrounded them that such a sight seemed no longer shocking.

The act of remembering the incredible travesties of our histories is excruciating. Entering an exhibition about the art of the Holocaust isn’t a pleasurable art-viewing experience, as many of us hope and want an exhibition to be. But these works do something that almost nothing else in the history of art can-- they allow us to act as witnesses to events that many have tried to brush aside, to gloss over, to forget about. And that’s why it is all the more important that there are cultural institutions who seek to preserve and document the artwork made by those living in concentration camps, ghettos, and labor camps. It’s a testament not only to the fact that these atrocities did occur, but that these people-- the artists, and their subjects-- actually lived and endured this suffering. While some of the artists from the Holocaust, like the ones I’ve mentioned today, were able to sign their works of art for posterity, the vast majority of artworks from concentration camps were uncredited, forged by men, women, or children unknown. Some may have done this purposefully to separate themselves from their works, to avoid identification should their secret art be discovered. But most? They’re just lost to us, and lost to history-- not on purpose but by the cruel hand of fate. What remains are these works of art-- the only way that we can work to fill in some of these gaps- to help us remember and to understand.

At the beginning of this episode, we began with the words of Anne Frank, a victim. Here, we’ll end with the words of Elie Wiesel, a survivor. Forgive me for falling back on literature here-- and perhaps my reliance on the written word is a clear example of why writing, not visual art, is most closely associated with Holocaust remembrance and art. It’s just… easier, at least for the reader. But, back to Mr. Wiesel. In Night, he writes, quote, “For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living. He has no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory. To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

Thank you for listening to this episode of the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal, with additional writing and research by Patricia Gomez. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com. Research assistance is by Stephanie Pryor, and social media help by Emily Crockett. Our production and editorial services are provided by Kaboonki Creative. Video. Content. Ideas. Learn more at kaboonki.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is an interdisciplinary creative space, founded to foster artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition spaces, Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator. This means that you can donate to the show and it is fully tax-deductible! Do you like this show? Show you care, and consider donating just $3-- that’s less than a good coffee at Starbucks-- to help us keep doing what we’re doing. Follow the “Donate” links at our website for more details, and thank you. By no means do we profit from this podcast-- but we sure would love to keep it going.

Speaking of website, you can also go there for images, information and links to our previous episodes. That site is artcuriouspodcast.com. And you can contact us via the website, email us at artcuriouspodcast@gmail.com, or find us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod. --and remember to subscribe and review us on iTunes. It truly helps people to find our show. Check back in two weeks as we continue to explore the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in art history of the World War Two Era.