CURIOUS CALLBACK: The Wild and Wonderful World of Weegee

In this “Curious Callback” episode, we’re revisiting one of our favorite weirdos—Weegee!— whom we featured in Episode 5, alongside Andy Warhol. Today, Weegee gets his full due with a deep dive into his life and work.

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts and FOLLOW on Spotify

Don’t forget to show your support for our show by purchasing ArtCurious swag from TeePublic!

SPONSORS:

The Zebra: compare home and auto insurance on one independent marketplace, for free

Woodstock Chimes: Use promo code “ARTCURIOUS” for a 15% discount on your order

BetterHelp: Listeners enjoy 10% off your first month of counseling

Storyblocks: Get unlimited downloads at Storyblocks, a subscription-based provider of stock video and audio

Episode credits

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Logo by Dave Rainey.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits

"September" by Kai Engel is licensed under BY 4.0; "Orpheus' Awkwardly Buttoned Duffle Coat" by Ergo Phizmiz is licensed under BY-NC-SA 4.0; "Rendezvous (ID 346)" by Lobo Loco is licensed under BY-NC-SA 3.0 DE; "Lay Here in the Dusk" by Marrach is licensed under BY-NC-SA 3.0 US; "Blur The World" by Tagirijus is licensed under BY-NC-SA 4.0; "PLANET PLUTO" by Jared C. Balogh is licensed under BY-NC-SA 3.0; "Relinquish" by Podington Bear is licensed under BY-NC 3.0. Ads: "Dakota" by Unheard Music Concepts is licensed under BY 4.0 (Betterhelp); "Gourd Hunting" by Jesse Spillane is licensed under BY 4.0 (Storyblocks).

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Links and further resources

Episode Transcript

Even though it’s springtime and the flowers are starting to bloom and the birds are signing, I still feel like I’m yearning for a spookier time of year. nothing makes me feel cozier than curling up with a creepy book about ghouls and goblins. This Halloween-yearning not only infiltrates what I want to watch and what I read, but it also affects what kind of art I’ve been enjoying. In particular, I’ve been curious about the myriad ways that we can portray death in visual art. Because death has always been a part of art history. So much of the great art that we know and love today works in the capacity to stave off one of the terrible side effects of death-- being forgotten. Portraits, stone monuments, ancient coins-- they all aim to ensure that the subjects depicted will be remembered and revered for all eternity. There’s funerary sculpture and death masks that tackle death directly as their bread-and-butter. And then there are artists who brought concepts and philosophies of death into the modern era-- with people like Ana Mendieta, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Damien Hirst, and Andreas Serrano getting in our faces about the fact that we are all going to die someday. But one artist really takes the cake in terms of focusing on the everyday tragedy of death as a subject in a very revealing and even exploitative extent. Many people might jump to say, “Oh, Andy Warhol!” And indeed, Warhol loved to glamorize death in his works-- from replicating tabloid images of car crashes and aviation accidents to these truly chilling portraits of electric chairs. But was he the first to truly make death his calling card? Nope. That honor belongs instead to an immigrant photographer working in Manhattan in the 1930s and 1940s.

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, crazier, or more fun than you can imagine. Today, as we continue to work hard on our upcoming season, we’re revisiting and tweaking some of our favorite early episode. This is a deep dive into the story of Weegee, the subject of our fifth episode. This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

Weegee, of course, wasn’t the actual name of the artist we’re discussing today-- but we’ll get to that nickname shortly. The man who would become Weegee was born Ascher or Usher Fellig, though he eventually went by the Americanized name of Arthur Fellig. Fellig was born on June 12, 1899 near Lemberg, Austrian Galicia, now modern day Zolochiv in Ukraine. When he was 10 years old, Fellig emigrated with his mother and siblings to New York City, following in the footsteps of his father, who had come to the country three years prior to establish roots. This was at the dawn of the 20th century when immigrants from Eastern Europe--and elsewhere, of course-- were not welcomed with open arms, but Arthur Fellig didn't let his outsider status affect him, and indeed, he worked extra hard to overcome it, dropping out of school in his early teens to work odd jobs to support his family so that they could live as secure a life in America as possible. Somehow, serendipitously, one of his first jobs was working as a street photographer, taking pictures of children riding a pony. He would then sell the pictures to the children's proud parents at a markup of 50 cents for three photographs. As Felling later told his friend, fellow photographer Ralph Steiner, “It was a good racket, but the pony ate too much.”

He fell in love with the camera almost immediately, and was hired quickly to act as an assistant to a commercial photographer in the early 1920s. During that decade, he did almost everything that he could do with photography--developing, printing, editing, selling, and creating. His biggest coup came in 1924, when he took a job as a dark-room technician at Acme NewsPictures, which later became United Press International Photos. He juggled this and several other low-paying jobs, which gave him just enough free time so that if he limited the amount of sleep he got every night, he could have the chance to go out into the darkened city and shoot his own images.

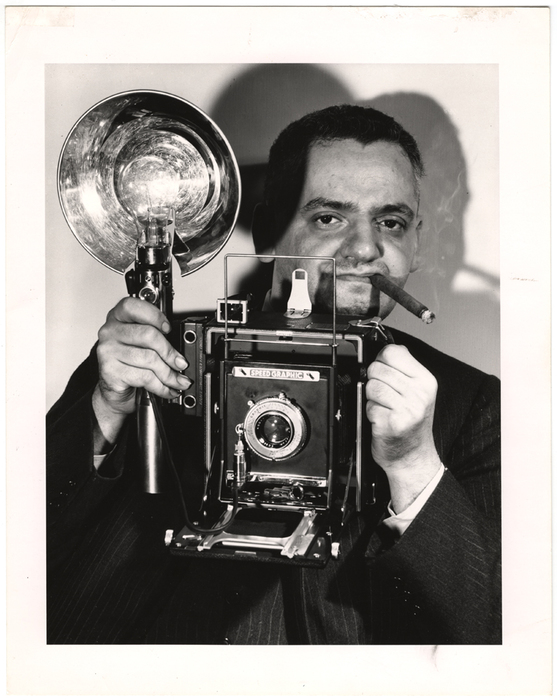

Fellig’s nocturnal ramblings around New York City with his camera morphed him quickly into a rather strange fellow. But instead of letting his curious personality become a liability, he embraced it, and crafted and cultivated a very specific persona meant to garner attention. By the time he was in his early 30s, he was overweight, brash, with uncombed hair, and never without his favorite vice-- a cigar, of which he would usually smoke up to 20 per night, according to reports. He was instantly noticeable-- and word of his photographic talents got around, quickly. As his career progressed, he would eventually make enough money to keep himself comfortable, particularly since he married only In the last years of his life and did not have children of his own, and because he lived mainly for his work. He sold his photographs to many of the top newspapers, magazines and tabloids of the day, and he was paid handsomely for it, sometimes receiving $5 per picture, which was a pretty penny for an image back in the 1930s and 40s. He was published by the New York Post, the Daily News, the Herald-Tribune, the World Telegram, and beyond. But he was always very careful to not let on whether or not he was financially stable. Probably this was his attempt to stay identifiable with the Everyman, as he most often covered the events or causes with happened to the lower classes instead of those of the elite, like other celebrity-obsessed tabloid photographers roaming New York at that time. And to me, that’s one of the beauties of Weegee’s works-- his images are democratic-- crossing class and race lines and with no particular social or political affiliation, though most of his works are pretty closely tied to the working class. So it makes sense that he’d make himself look a little shabbier. And he really took this to a whole new level-- To seem more like a member of the working class, for example, Fellig would later take all of his suits to a tailor who would add at least two inches of fabric to the entirely of the outfit. This made it appear, according to editor and columnist Allene Talmey, “as if it had been bought off of a pushcart on New York City’s Orchard Street.” He lovingly called himself “the gentleman bum.”

In the 1920s, Arthur Fellig was working by day at Acme NewsPictures and carefully crafting his photographic style in his off hours. In those photographs, he actively searched for his own version of America, his take on the everyday life of those Americans who surrounded him every day. And what would become the everyday of Fellig was darkness- literally. We’re talking most specifically about night--the time of day when Fellig would perform his photographic walkabouts. Though he didn't exclusively shoot in the evening, it is really these photographs that we think of when we think of Weegee: shadowed alleyways, darkened movie theaters, shuttered storefronts, and crowded streets, with their inhabitants all starkly illuminated by his flashbulb and provided what he dramatically called “Rembrandt lighting.” He began to hone his style, manufacturing spontaneous black-and-white images that focused many times not only on that literal darkness of the environment, but on the metaphorical darkness of urban life. He could frequently be found at the scene of a terrible fire, a murder, a car accident, and the images he created there are seemingly equal parts exploitative and detached. His photographs could capture the aftermath of a grisly death destined for the tabloids of the day, but they were also just documents of the event itself, too. And much of the time, the scene of the crime or the burning building wouldn't even be his subject matter. Instead, he focused predominantly on the human element. As Ralph Steiner wrote, “Early in his career he discovered that most corpses and fires look pretty much like one another….now he looks first for the human element, for anything incongruous, for little points which may be more interesting and revealing than the main event.” So Fellig turned his lens towards the policeman carrying out newborn kittens from that burning building, or to a scene of onlookers rubbernecking a crime. These scenes can be humanizing, but then others are very film noir-- policemen peering over crime scenes in their fedoras, pavements darkened by spilled blood, and even images such as one of my favorites: of a stone-faced, fur-wearing woman whom the photographer would identify in his capital-letter scrawl in the margins as “the murderess.”

It wasn't all tragedy and debauchery with Arthur Fellig, though. Some of his most engaging images are of children cooling off in the spray of a fire hydrant on a hot summer day, or of couples kissing in the midst of a crowded movie theater. He photographed people laughing at a bar, dancing in Harlem, and leaving the opera. But it is his images of the grittier realities of the city at night that transfix viewers. And the man who would soon style himself as Weegee felt more at home in this space. He once said, “Sometimes a night goes by with no murder and it don't seem right to me. I think something’s wrong.”

Fellig recognized that he had a good thing going. He had a style that was eye-catching and his works were in demand. So in 1936, he left his various odd jobs in favor of something entirely different-- to become a freelance photographer-- and that changed everything. About his newly independent method of working, Weegee said, “In my particular case I didn't wait 'til somebody gave me a job or something, I went and created a job for myself—freelance photographer. And what I did, anybody else can do. What I did simply was this: I went down to Manhattan Police Headquarters and for two years I worked without a police card or any kind of credentials. When a story came over a police teletype, I would go to it. The idea was I sold the pictures to the newspapers. And naturally, I picked a story that meant something.”

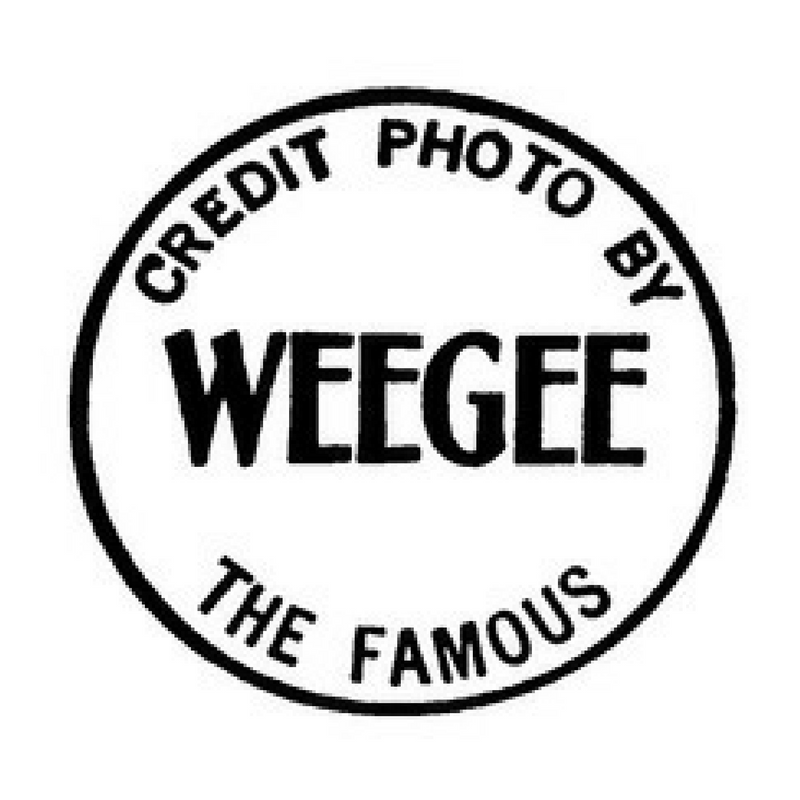

Fellig’s involvement with the police teletype was integral to his work-- and integral to his nickname and branding. At the beginning, he did spend a lot of time simply skulking around police headquarters, waiting for a tip-off about the latest crime scene, but eventually he was granted access to his very own police teletype machine-- a kind of electric typewriter that would transmit messages from point to point, almost like a precursor to a fax machine. And Arthur Fellig was actually one of the very first civilians in history to have one of his own. And in true Weegee style, he really took it to the next level in its use. He set up house in an apartment across the street from police headquarters in Manhattan, and installed his teletype by his bedside. He left it on all day and night, and would jump to action anytime a noteworthy event came to his attention. It was said that somehow he even seemed to wake up from a dead sleep to get the best scoop-- almost as if he knew a crime was being committed before the police even learned about it. Later, when he bought his own car, he installed his own police radio therein so that he could drive around all hours of the night and arrive at any crime scene or happening far earlier than his competitors from any tabloid or newspaper. And it is by this seemingly supernatural ability to arrive almost right after a crime had been committed that Weegee received his nickname-- a phonetic spelling of the popular fortune-telling Ouija board game. Instead of O-U-I-J-A, Weegee spelled his moniker “W-E-E-G-E-E-.” Weegee, to which he would later add the superlative “The Famous.” Weegee the Famous, he called himself, in a both ironic and clearly non-ironic fashion. And thus, the branding of Arthur Fellig was complete.

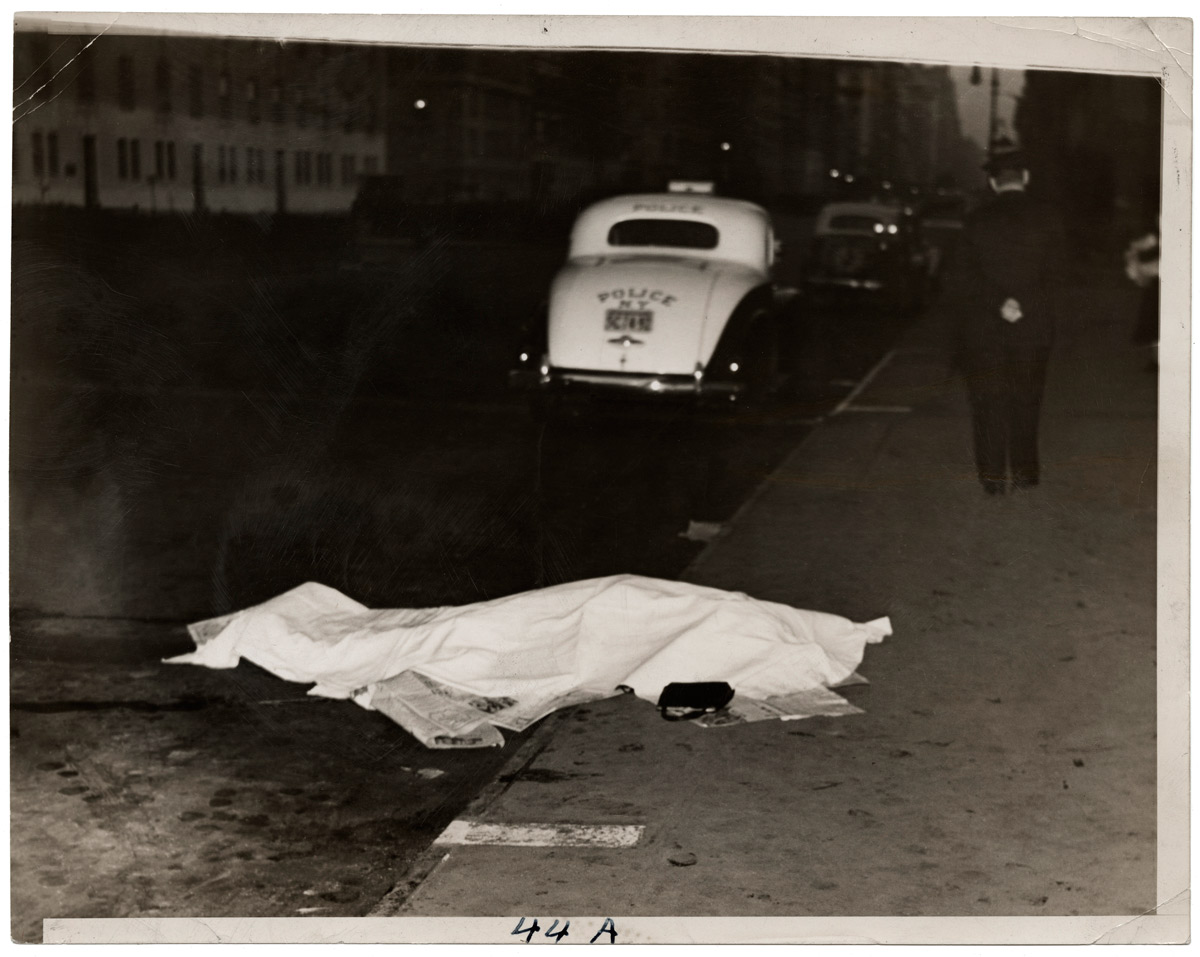

If there is one single thing that made Weegee really stand out, it is this: murder. He once very famously quipped, “Murder is my Business.” And indeed he really made it his most profitable line of work, capturing not only the aftermath of a deadly confrontation, but also the grittiest details: a crumpled car destroyed by a terrible crash; a bloodied corpse haphazardly lying on a sidewalk; perpetrators being taken away in shackles. With such in-your-face images, Weegee is meant to grab your attention immediately-- and even today, over 75 years later, his images still mesmerize. Certainly that was a major selling point to New York’s many tabloids, who paid top dollar for the grizzliest of Weegee’s works. The old adage about television news-- if it bleeds, it leads-- was something that Weegee could set his bank account by long before there even was televised news, and if you’ll pardon my terrible pun, he really made a killing at his work.

A good example of Weegee’s photos is this--a piece simply titled Murder Victim, circa 1940. Lit by Weegee’s stark flashbulb, it’s a quick glimpse of a policeman’s lower body, a mangled, open-shirted corpse, and a distressing baby carriage parked in the background. It’s a moment captured-- there’s nothing posed about it. One can really just visualize Weegee bursting forward past any police lines to grab the quickest snap possible. And that very sensation of quickness just brings home the veracity of the image-- this was real life. This was a crime scene. This person really lived and died-- and Weegee was there, in our place, to act as witness and to capture the moment for generations to come. This is one of Weegee’s images where a murder victim is not identified to us. For many of the crimes which he documented, he was able to garner information from the police and passersby: who were the victims and perpetrators? What happened here? And in some cases, he was almost more excited and star-struck when the individuals were connected to something especially seedy-- like organized crime or prostitution rings. And indeed, Weegee’s identification of, and near celebration of, those who would dwell in these pseudo-underworlds would prefigure the the cult of celebrity which would eventually become hugely important to Weegee.

As horrifying and grotesque as these blatant murder images are, to me, there’s almost nothing more awful than a work like this one-- one of Weegee’s most famous photographs. This is a picture titled Their First Murder. This particular photo doesn't even show a murder at all-- instead, we see a group of children--probably aged between 7 or 8 and upwards to 15 or 16 years old-- as well as two women, reacting wildly to witnessing a murder. In Weegee’s first book, published in 1945 and titled Naked City, he did pair this image with one on the following page of the corpse lying in the street. But it is really Their First Murder that strikes our attention. It’s hard to look away from the faces here. In his book, Weegee wrote a one-liner to describe the scene as he remembered it, saying, “A woman relative cried… But neighborhood dead-end kids enjoyed the show when a small-time racketeer was shot and killed.” A couple of the children in the photo are outright laughing at what they've seen; a small group in the middle consists of a brunette girl straining, with manic, wide eyes, to get a better look, with another child’s hand pulling at her from behind-- perhaps tugging at her hair, either to get her away to safety, or to vie for a better viewing position himself- and it is probably the latter. A blond boy at the far left mugs for the camera, smiling hugely-- this is his moment to be memorialized. Others just outright stare. The kids remind me that their response and reactions are not yet molded by behavioral expectations, nor are they mature enough, possibly, to fully understand what they've just seen. The two women, though, are in direct contrast to the children-- they act appropriately for witnessing the end of a life-- anguish, down-turned eyes, tears. And that's what I find to be one of the most interesting and unique elements of Weegee's work. Weegee himself photographed in a dispassionate way-- but the people he photographed are so emotive and expressive that I find myself standing not in the photographer's shoes, but in the subjects shoes. Weegee doesn't act as a substitute for us as viewers, like many photographers do. Instead, he mirrors our own emotions and tendencies back to us. And for me, the responses captured by Weegee and what they might mean for us, as viewers, are what make his photographs disturbing.

Coming up next, it’s the legacy of Weegee- how he got his big art world breaks, defected to Hollywood, and inspired Joe Peschi, and Jake Gyllenhaal. Stay with us.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

Weegee focused his lens on the violent tragedies of everyday life-- particularly the everyday lives of working and lower-class citizens of post-Depression New York-- and, somewhat dispassionately-- sensationalized it, capitalized on it,... and elevated it. You see, Weegee was not only popular in the truest sense, meaning that his tabloid-fodder images were sought after by the same working folk he photographed, but they were also praised by the fine art community, too, for his dramatic style and technique - and this popularity on both fronts occurred during his lifetime, not after the fact. Which, if you think about it, is not the norm for most artists. In 1941, New York City’s Photo League held the first exhibition of Weegee’s work, and shortly after that, in 1943, MoMA, the Museum of Modern Art, began collecting his works and showing them in a museum for the very first time. As one can imagine, Weegee was thrilled with the fact that he was beginning to be shown and collected by esteemed institutions throughout the city, and he took his own involvement in the shows seriously-- for the Photo League show he even designed these infamous wall displays with splashy, sensational text, and even went so far as to drop red paint down the side of his installations to remind viewers of spilled blood. But these exhibitions had an extra element to them, as well-- they served as a celebration and praise of Weegee himself. Remember, Weegee called himself Weegee the Famous-- and it's also true that a significant portion of Weegee’s artistic output were self-portraits. He was his own best subject-- his favorite subject, really-- and he knew that he was doing something new, different, original. He was firmly a part of the scene in which he was photographing, and indeed, he felt that a crime --especially a murder-- wasn’t complete until he documented it. As he once wrote, “No bumping off was official until I arrived to take the last photo, and I tried to make their last photo a real work of art.” Weegee the Famous was the key, he thought, to it all.

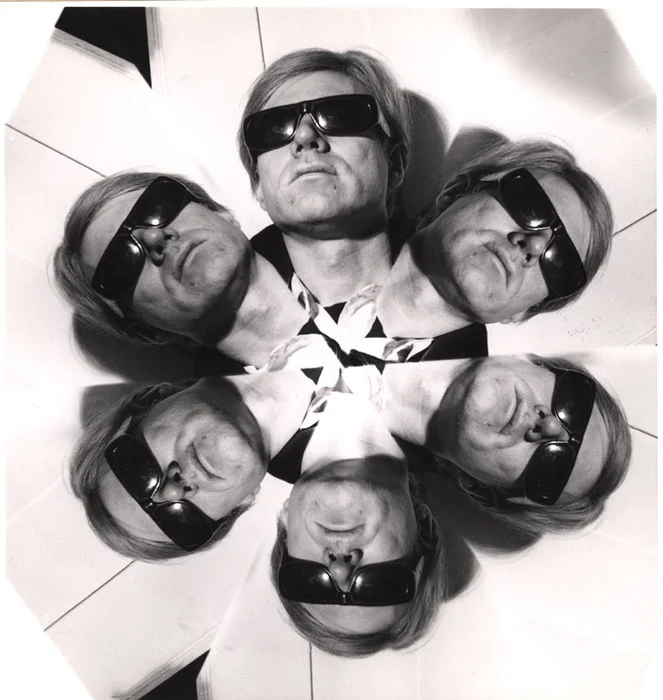

One of the nice things about using yourself as a subject is the immediacy and ease involved-- wow, you have someone here to photograph, whenever you’d like to photograph him or her! And this sense of immediacy also lends itself to spontaneity and experimentation-- so it shouldn’t be surprising that Weegee used his own images to try out his newest and latest techniques. One of his innovations in the early 1940s was what he would eventually call his “elastic” lens-- which was actually a combination of a bendable lens and a variety of filters, mirrors, and even kaleidoscopes to distort his images. Figures or individual parts of such figures are duplicated, made to disappear, elongated or truncated. It became an obsession for Weegee, and became an even bigger part of his oeuvre after he decided that he had had enough of the darkness of Manhattan-- its murders, its gangsters, and those grimy, gritty, flash-lit nights-- and moved to the big lights and bright stars of Hollywood. For just over four years-- from late 1947 to early 1952, Weegee mingled with actors, singers, politicians and writers, taking their pictures en lieu of bank robbers, crash victims and detached onlookers. But this new phase of his career wasn’t about taking images of all the pretty people-- in fact, it was about the opposite. it was about using those “elastic lenses” on them, as he had done to himself, and create these bizarro portraits of everyone from Clark Gable and Ed Sullivan to, later, Jackie Kennedy and Johnny Carson. As he described it, “I had to have a lens out of this world to do justice to the strange sights and people which are Hollywood.” His most iconic became a series of images he completed of Marilyn Monroe from the early 1950s-- she who was at the height of her powers and popularity, and was seen as the voluptuous ideal of American beauty. But instead of celebrating that beauty, he purposefully hides it-- transforming an image of Marilyn with closed eyes and puckered lips, warping it so that her mouth is squeezed small and slightly off-center, and her nose is transformed into a pig-like snout. In another version, her nose is squeezed into a tiny line, her eyes pulled sharply together-- Marilyn Monroe via a funhouse mirror. All of these images are comedic-- for me, my first instinct is to laugh at them-- but then I quickly find myself grimacing, because these distortions are harsh. There is a darkness there-- an interest more in finding and focusing on the ugly than in the beauty that surrounds us. Because beauty really isn’t something that Weegee found interesting at all. In an interview, he once dismissed it entirely, stating, “Everybody likes beauty, but there's ugliness. Don't forget, it's human.”

That ugliness of humanity is the one thing that pervades all of Weegee’s works, from beginning to end. Even when he wasn’t distorting a celebrity’s image, he would focus instead of an unattractive facial expression, or a harsh angle, or even the lesser-enticing hangers-on in a celebrity’s orbit. It’s playful and satirical, a little bit rude, and totally irreverent. But when so many others-- like Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz--were systematically teasing out the beauty in every curve, line, and shadow, what makes Weegee so memorable is that he specifically ran the other way. His Hollywood works aren’t as popular or as praised as his New York pictures, but they are still an important part of who Weegee was-- all about the hustle, about highlighting what you’d rather be hidden, about that ugliness and darkness. In Hollywood, he went about the same themes that he pursued in New York, but did it from a different angle.

Hollywood, though, wasn’t meant for Weegee forever. In 1952, he moved back to New York City, and it was there that he spent the majority of his remaining years. The funny thing is that even though Weegee left Hollywood, Hollywood never ended up leaving Weegee- and his years spent there affected what he ended up doing for the rest of his life. Returning to New York, he felt that he couldn’t be the same dead-eyed Street photographer that he was 10 years prior. He had changed and experimented and was eager for yet another new challenge. He thought back to his time in Hollywood- and the metaphorical light bulb lit up. The movies! Though he was still working as a film photographer, and even lectured frequently both in the US and in Europe on photography theory and practice, his passion had shifted to film. It wasn’t too much of a stretch- and in fact, it appears that he had been experimenting with 16mm film as early as 1941.While he was in Los Angeles, the film bug really took hold – not only for himself as a filmmaker, but also, apparently, as an actor. He was cast first in a role that makes an awful lot of sense- he portrayed a street photographer in the 1948 film Every Girl Should be Married, and followed up with an uncredited role as a boxing ring timekeeper in the 1949 film The Set Up. And in fact, all of his acting gigs- about seven in total, were uncredited, except for one- an oddball 1966 pseudo-documentary slash sexplotiation film featuring Weegee as a version of himself as a photographer and woman-chaser. This movie, called The Improbable Mr. Weegee, was a so called “nudie cutie” film that was equally ridiculous and slapstick. It was Weegee’s first and only starring role, and by all accounts, it is pretty terrible.

But if there is only one major Hollywood gig that we can choose to remember Weegee’s cinematic period by, then we have lucked out, because there happens to be a surprisingly worthwhile entry in his filmography. In 1964, he was billed as a technical consultant to one of the most famous directors in the history of film and in one of that director's most famous movies: he was a consultant for Stanley Kubrick in Dr. Strangelove. Kubrick, like so many others, was blown away by Weegee’s New York Street photography- The grittiness, the harsh lights, they blinding whites and inky blacks. A film about the bombing of all humankind needed an aesthetic that was like a jolt – so who better than Weegee to inspire that dramatic aesthetic? But that wasn’t all that Weegee ended up inspiring on set. Legend has it that actor Peter Sellers was so intrigued by Weegee’s totally unique accent- German by way of the lower east side - that Sellers imitated it in order to give his character his own unique way of speaking.

Weegee died in New York City in 1968 at the age of 69, but his legacy has loomed far beyond and he influenced many artists- especially other photographers- who came after him. One look at Diane Arbus’s beloved weirdos on the outskirts of society- the vacant stares of people loitering in public parks or street corners- and you can see Weegee’s legacy. Robert Franks iconic late 1950s series, The Americans, might not have been as possible without Weegee’s street photography from two decades prior. And of course, let’s not forget the mid-20th century’s top provocateur who was equally fascinated with death and celebrity as Weegee was: Andy Warhol. I love the comparisons between Warhol and Weegee so much that I actually discussed these two in an earlier episode of the ArtCurious podcast – that’s episode five, if you want to go back and listen, and there you’ll learn about how these two are much similar then they might appear to be on the surface. Even today, a new generation of photographers is discovering his works for the first time, and taking them to heart. And of course it’s not just his aesthetics that have had A lasting impression. It is also his oversize personality, and his way of working. Peter Sellers wouldn’t be the last actor who was inspired to mimic Weegee on the big screen – Dario Argento’s 1991 film, Two Evil Eyes, presents us with a character modeled after Weegee and played by Harvey Keitel. Keitel’s character is called Rod Usher – Usher being an almost a blatant reference to Weegee’s birth name, Ascher Fellig. In the film, Usher is a crime scene photographer who proclaims, “still life is my art,“ which mirrors Weegee’s famous saying of “Murder is my business“ while punning on the art term of still life and the fact that a corpse is a literal representation of a still life. See what they did there? And then the next year, Joe Pesci’s Leon "Bernzy" Bernstein, also a crime scene photographer, was modeled even more directly after Weegee, right down to the iconic stogie, in the film The Public Eye. At one point, Bernstein gets to a crime scene so suddenly that the onscreen cops marvel that he must be using a Weegee board to divine crime locations.

in 2014, Weegee once again inspired a Hollywood blockbuster in a film that updates his temperament and style to the 21st century’s 24 hour news cycle. Instead of a crime scene photographer, Jake Gyllenhaal’s Louis Bloom in Nightcrawler is a freelance shooter of documentary news footage who sociopathically takes his job to the extreme- and, like Weegee, tries to sell his images to the highest bidder. Weegee was nothing if not the most fundamental capitalist when it came to his work. He once claimed, “ If I had a picture of two handcuffed criminals being booked, I would cut the picture in half and get five bucks for each.”

Truly, you can see these ripples of Weegee’s powerful work all throughout visual culture. And though Weegee once famously said that practically anyone could make photographs like he did, there could only ever be one Weegee the famous, who called himself the greatest photographer in the world.

Thank you for listening to this episode of the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, and our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com. Our production and editorial services are provided by Kaboonki Creative. Video. Content. Ideas. Learn more at kaboonki.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is an interdisciplinary creative space, founded to foster artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition spaces, Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator. This means that you can donate to the show and it is fully tax-deductible! Follow the “Donate” links at our website for more details, and thank you.

As always, you can also go to our website for images, information and links to our previous episodes. That site is artcuriouspodcast.com. And you can contact us via the website, email us at artcuriouspodcast@gmail.com, or find us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod. --and remember to subscribe and review us on Apple Podcasts and tell anyone you want about the show. Check back in two weeks as we continue to explore the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in the shocking works of art history.