Episode #97: Cherchez La Femme, or The Woman Behind the Art--Anna Whistler (Season 11, Episode 6)

In Season 11 of ArtCurious, we’re highlighting the lives and work of the women who supported some of the world’s favorite artists. Today, you know her face, but you might not know her name, or much about her life—meet Anna Whistler, the mother of American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts and FOLLOW on Spotify

Don’t forget to show your support for our show by purchasing ArtCurious swag from TeePublic!

SPONSORS:

Bombas: get 20% off your first order with our link

Indeed: Listeners get a free $75 credit to upgrade your job post

Betterhelp: Get 10% off your first month of counseling

GEM Multivitamins: Get 30% off your first order

Magic Mind: Get 40% off this “magical little elixir” with code ARTCURIOUS

Want to advertise/sponsor our show?

We have partnered with AdvertiseCast to handle our advertising/sponsorship requests. They’re great to work with and will help you advertise on our show. Please email sales@advertisecast.com or click the link below to get started.

https://www.advertisecast.com/ArtCuriousPodcast

Episode Credits:

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Logo by Dave Rainey. Additional music by Storyblocks. Research help by Mary Beth Soya.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Episode Transcript

I don’t know about you, but I learned an awful lot about art, opera, folk tales, and even history from one particular source while I was growing up—and that wasn’t school, or at least it wasn’t always school. Nope. I learned about all that cultural goodness from cartoons, especially Looney Tunes and shorts from Disney’s acclaimed Golden Age of Animation. I learned about Richard Wagner from the cartoon where Elmer Fudd chases Bugs Bunny around, singing “Kill the Wabbit.” I first learned of Rudyard Kipling through Disney’s interpretation of his 1894 title, The Jungle Book. And I got my first glimpse of one of the most famous paintings in American history through a Donald Duck short titled “Donald’s Diary.” It features Donald reminiscing about the development of his relationship with his lady love, Daisy Duck, and involves a scene where Daisy introduces Donald to her parents. Her mother is seated in a blue-walled room, seen in profile in a severe black gown and white head covering, her feet propped up on a box and a book plopped on her lap. Here she is, Daisy Duck’s mother, a figure that we probably had never seen before in Disney cartoons, but we know her right away, because we understand the reference. She’s not just Daisy’s mother. She is Whistler’s Mother. And she made Whistler a household name.

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings, and photographs are weirder, more outrageous, or more fun than you can imagine. In ArtCurious Season 11, we’re highlighting the lives and work of the women who supported some of the world’s favorite artists. Today, you know her face, but you might not know her name, or much about her life—meet Anna Whistler, the mother of American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler. This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

It feels like it’s impossible to talk about James Abbott McNeill Whistler without talking about his mother, because his mother—or at least the portrait he made of her—is Whistler, is the icon representing what a Whistler painting is; just like—whether fairly or not—we can’t or rarely do talk about Leonardo da Vinci without bringing up the Mona Lisa, who is kind of like a sister to Whistler’s Mother in terms of being over-hyped, over-familiar, and not understood enough. But now’s our opportunity to change that by learning more about Whistler’s stern-looking, black-berobed mother, a chance to transform her from two-dimensional symbol to a three-dimensional person.

Anna Mathilda McNeill was born in September 1804, as one of six children of Charles Daniel McNeill, a Scottish physician, and Martha Kingsley McNeill, a British woman whose family had loyalist ties during the American Revolution and became active as slave traders in the late 18th century. Anna McNeill was born, like most of her siblings, in Wilmington, North Carolina—not too far from where I am now—and like most American girls of her age, she didn’t get much in the way of a formal education, but learned the kind of things typically seen as important in order to catch a suitable mate when she reached marriageable age: music, poetry, some history, and cooking—all the things needed to be a good wife and a good manager of a bustling household. It turns out that from an early age, Anna McNeill already had her eye on someone special—someone for whom she hoped she could become that good wife: George Washington Whistler, a friend of her brother William. According to the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, Anna loved George Whistler, a West Point cadet, from the moment he met him—four years older, he must have seemed so worldly to the young girl. But Anna didn’t get the chance to marry him—at least not right away. He married Mary Swift—a friend of Anna’s—in 1819, and together they had three young children in the seven years that they were married before Mary died in 1827. Before she passed, Mary called her husband to her on her deathbed and demanded that if he were to marry someone else, quote, “it must be to Anna and no one else.” And the widower George Whistler made good on his promise. He married the twenty-seven-year-old Anna McNeill in 1831.

Fast forward a couple of years, and the Whistler family—George, Anna, and George’s three children from his first marriage—were based in Lowell, Massachusetts, where George worked as a civil engineer, during which he produced the earliest designs for a steam locomotive built in all of New England. Anna was home with the children, and by 1834 she had given birth to her first child: James Abbott Whistler, born in July of that year.

Anna Whistler would go on to give birth to five children, but only two of them—James, and her second son, William—survived into adulthood. Because of these losses, and possibly because James was her firstborn biological child, Anna was particularly tender toward him, even during a time when parents were about as stern as they were loving. James recalled that his devout Episcopalian mother disallowed toys at home, and only provided the Bible as reading material. Still, she was a devoted mother, and historians often like to point to a particular quote in her journal, now in the New York Public Library’s manuscript collection, that showcases gentleness as her primary parenting motivation. As she wrote, quote, “Gentleness is a mild atmosphere; it enters into a child’s soul like sunshine into the rose bud—slowly but surely expanding into beauty and vigor.”

Like many parents we’ve discussed on ArtCurious in the past, Anna Whistler encouraged her son in his interests beginning at a very early age. Once, when he was ill in bed as a child, she gave James a set of engravings by the British artist William Hogarth as a way to keep him entertained—and it did, with little James poring over the illustrations and keenly studying every nook and cranny of Hogarth’s satirical scenes. But it was a big family move when James was eight years old that made the biggest impression. His father, George, had been courted by Russian emissaries as the go-to guy when it came to building railroads—and when they invited him to oversee the establishment of a rail line between Moscow and St. Petersburg, George was thrilled—but he knew that he’d have to get his family on board, or else he wouldn’t go. So he let Anna make the choice: and she said yes—yes, we’re moving to Russia.

In general, St. Petersburg treated the Whistler family very well. They became immersed in upper-crust society, mingling with the Russian nobility and George Whistler even claimed Tsar Nicholas I as one of his pals. George received a pretty penny for his work—nearly $400 thousand in today’s dollars, which meant that the family lived well, and that James was well-educated, too. Anna, who had always encouraged her son’s artmaking, pulled for his admission to St. Petersburg’s Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, which James began attending at the age of 11. That he excelled was not a surprise to Anna, but it did prove wondrous to others. In Anna’s diary, she mentions the British artist Sir William Allan, who visited St. Petersburg and met James, after which he said to Anna, quote “Your little boy has uncommon genius.”

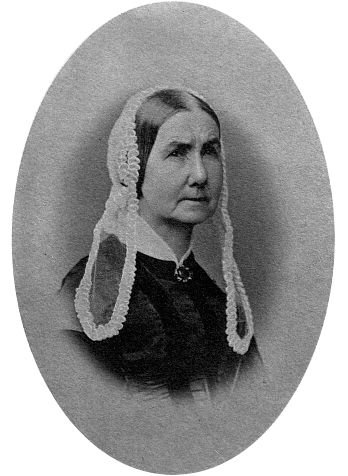

In 1848, St. Petersburg experienced a massive cholera outbreak, so George Whistler sent his family—including Anna and James—to England to wait out the infections, while George stayed behind. While in England, Anna arranged for continued art lessons for her son, but it wasn’t the same--James missed the color and opulence that St. Petersburg brought him. Unfortunately, his reappearance to Russia was only for a brief time. His father arranged for the family’s return after the cholera epidemic was thought to be past—but alas, it wasn’t, and George contracted the disease and died on April 7, 1849. Without their breadwinner, the Whistler family’s income dropped substantially, and Anna was forced to move the children back to the U.S. So distraught was Anna by the death of her husband that she committed herself, as some widows did at the time, to wearing mourning attire for the remainder of her life: a stolid black dress accessorized with a white muslin bonnet. It is the same garb by which she would be identified even more than a century later, when she was transformed into an iconic image of stately motherhood.

How did that iconic image of stately motherhood come about? That’s coming up next—right after this break. Come right back.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

The widowed Anna Whistler and her sons, James and William, settled first back in Connecticut before moving to Scarsdale, New York, trying to give her family the best that she could, and that included arranging for her eldest to follow in his father’s footsteps as a cadet at the famed West Point Academy. But James wasn’t that into the life of a would-be soldier, and so he dropped out, moving instead to London to study art. And it’s a good thing he did, too, because back in the U.S., the Civil War was a-brewin’, and once the Confederate States officially formed in 1861, Anna decided to hightail it out, too, settling in London to live with James.

In the case of many white male artists throughout history, James Whistler had the help of a good woman to manage his household so that he could focus his time on work. In Whistler’s case, for much of his life, and certainly during its most formative periods, like this time in London, that person was his mother, Anna Whistler. As author Sarah Walden notes in her book, Whistler and His Mother: Secrets of an American Masterpiece; An Unexpected Relationship, this was an arrangement that seemed to suit both parties rather well, with James working without interference and with Anna nurturing his talent and also keeping an eye on her son’s potential excesses, caring for what she termed “the every day [sic] realities,” so that James could soar, quote “upon the wings of ambition.” She even entertained his artsy friends when they dropped by—people like fellow artist Dante Gabriel Rosetti, whom we mentioned previously this season in episode # 94 about Elizabeth Siddal. Walden writes that visitors were often struck by their mutual devotion: Anna indulged her son, and he liked it—and returned the favor by treating her with respect and occasional deference. But the role that probably no one had anticipated—not even Anna or James themselves—was that Anna Whistler would play muse in her son’s most well-known work of art.

There are a number of things that are truly fascinating about Arrangement in Black and Gray No. 1, the 1871 painting known to most of us today as Whistler’s Mother. The first is that there’s not a whole lot of information or documentation about the work itself. In the final years of his life, he sat down with his future biographers, the husband-and-wife team of Joseph Pennell and Elizabeth Robins Pennell, to share what Sarah Walden calls “a thousand delightful anecdotes,” but he shared almost nothing about his portrait of his mother—even though, by that time, it had gained enough acclaim and acceptance. But we’re getting ahead of our story a little bit. The point is, the story behind Whistler’s Mother is sometimes distorted, or even forgotten, because it’s hard for us to see it as it is, as it was. Like the Mona Lisa, it gets mythologized and has become over-familiar, appearing in those Donald Duck cartoons and everywhere else since its inception in the late 19th century.

Was Whistler’s Mother always going to be a portrait of… Whistler’s Mother? You might be surprised. Come back in a moment.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

How Anna Whistler ended up modeling for her son is a point of debate, and one that hasn’t been 100% proven. The traditional story, crystalized, for better or for worse, in Elizabeth Mumford’s 1939 biography, Whistler’s Mother; the Life of Anna McNeill Whistler, states that the painting was the product of a twist of fate. James Whistler hired a model, a 15-year-old girl named Maggie, for a stint of several hours, asking her to stand and pose as he made preparatory sketch after preparatory sketch. Maggie, apparently, grew tired of just standing there, and after complaining to the artist without effect and relief, she stormed off, leaving Whistler in a model-less lurch. So he asked his mother to stand in, temporarily, so he could continue finalizing some details and figure positioning. But being in one’s late 60s is not the same as being 15 years old, and as much as Anna surely wanted to help her son, she couldn’t stand nearly as long as even Maggie could, so she asked if she could sit down instead. James Whistler said yes—and liked the seated profile so much that he threw away his previous sketches, determined to create an all-new work with his mother—and only his mother—as its subject.

Elizabeth Mumford’s biography of Anna notes that the portrait was created with much silence and focus between Anna and James, with only the occasional grumble from the artist if things weren’t necessarily going his way. On occasion, when he was pleased with a day’s work, he would jump up from his easel, run over, and exclaim, quote, “Oh, mother, it is mastered, it is beautiful!” Now, Mumford’s writing style is very 1930s, seeming a little sappy for modern-day readers like me, but it is entirely possible that this was the reaction between mother and son, that the process of its creation was a quiet, calm one, and that both of them were thrilled with its finished appearance. (And can I just interject for a moment to say, wow—Whistler got his mother’s appearance right, because, as you’ll be able to see from photographs of Anna—which you can find on my website, artcuriouspodcast.com—she looks exactly like her painting). It worked out as well—if not better—than both of them could have hoped. As Anna would write, happily, quote, “Jemie [that was her pet name for him] had no nervous fears in painting his Mother’s portrait…for it was to please himself & not to be paid for in other coin!”

That Whistler made the work to, quote, “please himself and not to be paid for in other coin,” is an interesting statement, and I am unable to garner from Elizabeth Mumford’s biography whether or not that was written simultaneously as the work’s completion or as an afterthought. I mention this because we know that Whistler did try to sell the work. Like many Western artists during this period, being seen in one of the two greatest European art establishments—either the Paris Salon, or the British Royal Academy—was the ticket to the brass ring. It was the place for your work to be seen, and thus to grab the attention of wealthy patrons. But when Whistler submitted this piece for the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition in 1872, it was accepted—but only barely, and he knew it. The Academy considered it a kind of failed experiment, because British painting at this time was far more luxurious and grandiose—think something brighter and richer, like those of the Pre-Raphaelites, works that are hugely decorative and luscious and even a tad sentimental. There’s nothing of the sort going on in Arrangement. In both his mother’s appearance and in his style of painting, Whistler’s work here is austere, even severe. It’s an example of Whistler’s signature style, a style known as tonalism. Simplified, Tonalism was Whistler’s way of seeking what he thought of as the perfect harmony of an artistic composition, using a minimal, even potentially monochromatic, color palette and the strict balancing of objects in the space—how Anna is counterbalanced by the drape of the black curtain on the left side and the framed artwork, in its stark white mat, above her knees. That—more than the subject herself—was what Whistler found most important in his artwork. But to the Royal Academy, and to many of its viewers, Whistler’s painting was… just a portrait, they thought. And though some at the Academy did gravitate to it as a kind and gentle ode to familial love, others just didn’t get it. And from the start, Whistler had a bit of an uphill battle to have it accepted and acknowledged.

But eventually, his struggles paid off. Whistler showcased his mother’s portrait, his Tonal experiment, in several exhibitions, and even consented to its reproduction via print, so that it became a familiar and widely recognized work of art. Still, the actual painting itself, Arrangement in Black and Gray No. 1, remained unsold for 20 years, and to make just a tiny bit of money, the ever-broke Whistler eventually pawned the painting. But in 1891, the French government—in a forward-thinking moment of inspiration, purchased the work for 4,000 francs, which some have estimated to mean the equivalent of about $20,000 US dollars today. That’s not chump change— Whistler’s Mother became the first of the artist’s works to land in a public collection, and it also provided Whistler the honors of becoming the first American to have a work in France’s national collection.

Anna McNeill Whistler didn’t live long enough to learn that her portrait would be purchased by a foreign nation, that this work would single-handedly become synonymous with her son—and her—last name; that it would inspire a new generation of artists to work in minimalistic tones and quietly balanced compositions. A couple years after her portrait was completed, Anna’s health began to decline, not only because she was aging, but also because she worried constantly about her son’s finances. Over the next decade, she struggled with severe illness, moving finally to the Hastings, in the South of England—coincidentally, the same location suggested by Elisabeth Siddal’s friends and family as a salubrious place for those with health issues—and it was there that she died on January 31, 1881 at age 76.

Though James Whistler—who, by the way, officially added the “McNeill” to his name to honor his mother after her 1881 death—never became wealthy by any means, the belated acceptance of Arrangement in Black and Gray No. 1 meant that he did gain more credence, and thus more patrons. And more than that, he felt that his style and manner of creating finally received the attention he felt he deserved. In 1894, he wrote to a friend, commenting on his good luck. He wrote of seeing his painting on display at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris, saying, quote, “Just think—to go and look at one's own picture hanging on the walls of [the] Luxembourg—remembering how it had been treated in England—to be met everywhere with deference and respect...and to know that all this is ... a tremendous slap in the face to the Academy and the rest! Really it is like a dream.” It was dream that his mother—the woman who gave him life—gave to him, too.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal. HUGE thanks to Mary Beth Soya for her awesome research for this episode and for almost all of our episodes this season. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, and our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com. Our podcast is co-produced by Kaboonki - podcasts, creative video, and more. Subscribe to their show, Subgenre, a podcast about the movies, available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and at subgenrepodcast.com. Kaboonki: Leave your mark. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator, which means you can donate tax-free to “ArtCurious” to show your support. To find the donation links and for more details about our show, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod.

Check back with us soon as we explore the lives and works of incredible women who supported the unexpected, slightly odd, and strangely wonderful world of art history.