Episode #73: Art Auction Audacity-- Van Gogh's Portrait of Dr. Gachet (Season 8, Episode 5)

In our eighth season, we’re exploring examples of some of the most expensive artworks ever sold at auction considering why they garnered so much money, and discovering their backstories. Today: Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet.

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts!

SPONSORS:

The Great Courses Plus: Get free access to their entire library with my special link!

Indeed: ArtCurious listeners get a FREE $75 CREDIT to boost job posts

Kobo: Enjoy a 30-day free trial, and then a low monthly subscription fee of $12.99

Bloomberg Connects: Download Bloomberg Connects at the Apple App and Google Play stores to access museums, galleries, and cultural spaces around the world anytime, anywhere

Episode Credits:

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Logo by Dave Rainey. Additional writing and research by Jordan McDonough and Joce Mallin.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits:

"Cake" by Ketsa is licensed under BY-NC-ND 4.0; "Roger Moore" by TRG Banks is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal; "I Recall" by Blue Dot Sessions is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "Periwinkle" by Chad Crouch is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "Fae" by Meydän is licensed under BY 4.0; "Westerlund 1" by Scanglobe is licensed under BY-NC-SA 4.0; "Hiatus" by Bio Unit is licensed under BY-NC-SA 4.0. Ads: "Beaches" by Alex Vaan is licensed under BY 4.0 (Kobo); "West in Africa" by John Bartmann is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal (Indeed); "Brain Power" by Mela is licensed under BY-SA 4.0 (Bloomberg)

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show. Click on the list below, and thank you for your purchases!

Links and further resources

The Washington Post: “$82.5 MILLION FOR VAN GOGH”

The Art Newspaper: “Where is Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet?”

Widewalls: “The Most Expensive Van Gogh Paintings Sold in the Auction Room”

Artnet: “The Curious Case of Dr. Gachet”

Städel Museum: Finding Van Gogh podcast

Arts Journal: “‘Dr. Gachet’ Sighting: It WAS Flöttl!”

The Independent: “Missing Van Gogh feared cremated with its owner”

http://www.artsjournal.com/culturegrrl/2007/01/dr_gachet_sighting_it_was_flot.html

Episode Transcript

I was in my undergrad art history classes a long time ago--like, we’re talking a couple of decades now. That makes me feel reeeeeally old, but I still remember it like it was yesterday. I remember, especially, getting to dig into Vincent van Gogh’s life and works--because who didn’t love to hear all about Vincent, our beloved ideal of the tortured genius artist? One afternoon, a portrait by Van Gogh popped up in the slide presentation in class, and what was curious is that we didn’t really discuss the work in terms of its importance, or what it represented, or much else about it really. What we discussed instead was its value. How much money had been spent upon this single canvas. And that’s because it was a fascinating case study that, strangely, mirrors almost exactly a situation occurring right now. Here was a painting that broke all previous world records for the most expensive work ever sold at an art auction. And the exact whereabouts--and even the safety, perhaps even existence-- of the painting were then-unknown.

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, more outrageous, or more fun than you can imagine. This season, season eight, we’re exploring examples of some of the most expensive artworks ever sold at auction and considering why they garnered so much money, continuing with one of the first BIG sellers of the late 20th century: Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet-- and, even more fascinatingly, where it has gone. This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

As we have discovered thus far in this season of the podcast, every piece of art that is placed on an auction block at a prestigious house like Sotheby’s or Christie’s has an elaborate history from the day the paint dried on the canvas to the day the current owner claimed it. It’s a really great reminder that the story of a work of art doesn’t end with the death of the artist, or even when it is sold for the first, second, or seventh time. The provenance-- or the ownership and location history of the work of art throughout time, and continuing on in our present moment--adds to that story. And in some cases, it makes it even more important--or, as we’ll see in our episode today, even weirder and more mysterious. In this case, it’s not as simple as your typical provenance, where you trace the work of art from an artist’s studio to a gallery or collector, and onward, perhaps, to an art museum. Sure, you can do that with Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet, but then the trail goes strangely cold, strangely especially since it made the biggest headlines the world over after it was sold in the last decade of the 20th century. But we need back up earlier than that, first, because we’re getting a little ahead on our story.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the world was floored, aghast even, when the Portrait of Dr. Gachet sold at Christie’s in 1990 for $82.5 million. Now, compared to the $400-plus million dollars that was dropped on the purported Leonardo da Vinci painting, Salvator Mundi--more on that in my book, ArtCurious--that sales amount seems trivial, and even with an increased price of $160 million in today’s money when accounting for inflation, it’s obviously big--but not big enough. And yes, we should probably take a moment to reflect on the sheer ridiculousness of me noting that any amount of money with that many zeros in it could be considered “trivial,” but yeah. We’re in post-Salvator Mundi times, and these times are weird. Anyway, back to 1990. When Dr. Gachet sold at that $82.5 million price, it was a landslide, a breakthrough moment, breaking every single record for the most expensive piece of art ever sold at auction. In some ways, this was the event that changed art sales and has brought us to the complications of our present moment. It was the sale that would, eventually, bring us that staggering sale of Salvator Mundi. It started it all--the icon, for a good long time, of what a high-caliber art auction could look like. At that time, it was a shock to everyone. But I think there would have been no other person more surprised by such a sales price than the artist himself, a man besieged by mental illness and other health problems, loneliness and professional disappointment. It’s a fun game that many of us like to play: that wistful imagining of Vincent van Gogh, resurrected for a brief moment to take solace in the fact that he has become, posthumously, one of the world’s most beloved artists.

Vincent van Gogh is someone we have covered extensively on ArtCurious-- both podcast and book-- so I won’t go too deeply into his biography here today-- but do go back and listen to our episode that aired earlier this summer, 2020, when the story of Vincent’s life and death was voted by you, our listeners, as your number one favorite episode! You can get all the great backstory there. But regardless of whether or not you’ve heard that episode, it is probably a given that you’re aware of Van Gogh. He's an artist that continues to entrance and enchant millions today, the most blockbuster-y of blockbuster artists. His work draws immense crowds for any exhibition that features his works, and even immersive entertainment options that feature only projections of Van Gogh paintings-- like the incredibly popular (and super fun) offering at the Atelier des Lumières in Paris--sell out constantly. There’s no one like Vincent. And by the by, just so everyone is on the same page, I did a straw poll on Instagram a couple of months ago about how, as an American and an art historian, I should be pronouncing Vincent’s much-debated last name. Suffice to say-- unless you are Dutch, the pronunciation is… difficult. So I’m going to continue using the Americanized pronunciation of “Van Gogh.” And onward we go.

Again, if Vincent miraculously popped up today, he would probably be flummoxed by all the attention. He wasn’t terribly successful during his lifetime in terms of art sales, exhibitions, and general popularity, though he did indeed sell a couple of works, was known in art circles and did show some work, and counted several well-known folks, like Claude Monet, as his fans. But for the most part, he wasn’t where he wanted to be, professionally and personally, by the time of his death in July of 1890. Obviously, if we accept the idea of the artist as having been suicidal, then the months--or even just a few weeks--prior to his death, the artist was at a very low point, mentally. And that is the point during which a particular person came into his life: Dr. Paul Gachet. Gachet was a doctor introduced to the artist by Vincent’s brother, Theo. Now, Gachet seems to be one of those people who had his hand in a little bit of everything-- I’ve seen him discussed as a neuropath, a homeopath, a psychiatrist, and other variations, so it just might be that doctors in the late -19th century weren’t as specialized as perhaps they are today.

Gachet, in Theo van Gogh’s point of view, would be an asset to his brother--someone who could keep a close eye on him in Theo’s absence and could assist Vincent with his various health crises. Vincent was tentative about Gachet, writing to Theo about his first meeting with the doctor, saying, quote, “I’ve seen Dr. Gachet, who gave me the impression of being rather eccentric, but his doctor’s experience must keep him balanced himself while combating the nervous ailment from which it seems to me he’s certainly suffering at least as seriously as I am.” It’s not the first time Vincent would mention the doctor’s own mental issues, as we will soon see-- but nevertheless, in his next letter to his brother, Vincent sounded much more hopeful about his chance for improvement due to his relationship with Gachet. He moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, where the doctor primarily practiced, to be in close proximity to Gachet, who by then had even become the artist’s friend and artistic patron. For a while, it seemed to work-- for most of May 1890, the artist seemed generally happy and healthy, producing more works of art than in practically any other period in his short lifetime. And Dr. Gachet himself was the subject of two of these paintings, (and even the one and only etching Van Gogh ever made) though the authenticity of the second portrait has been debated over time. It made sense-- Vincent often liked to paint not only the sights around him, but the people, and he spent so much time with Paul Gachet that his interest in painting him must have been strong.

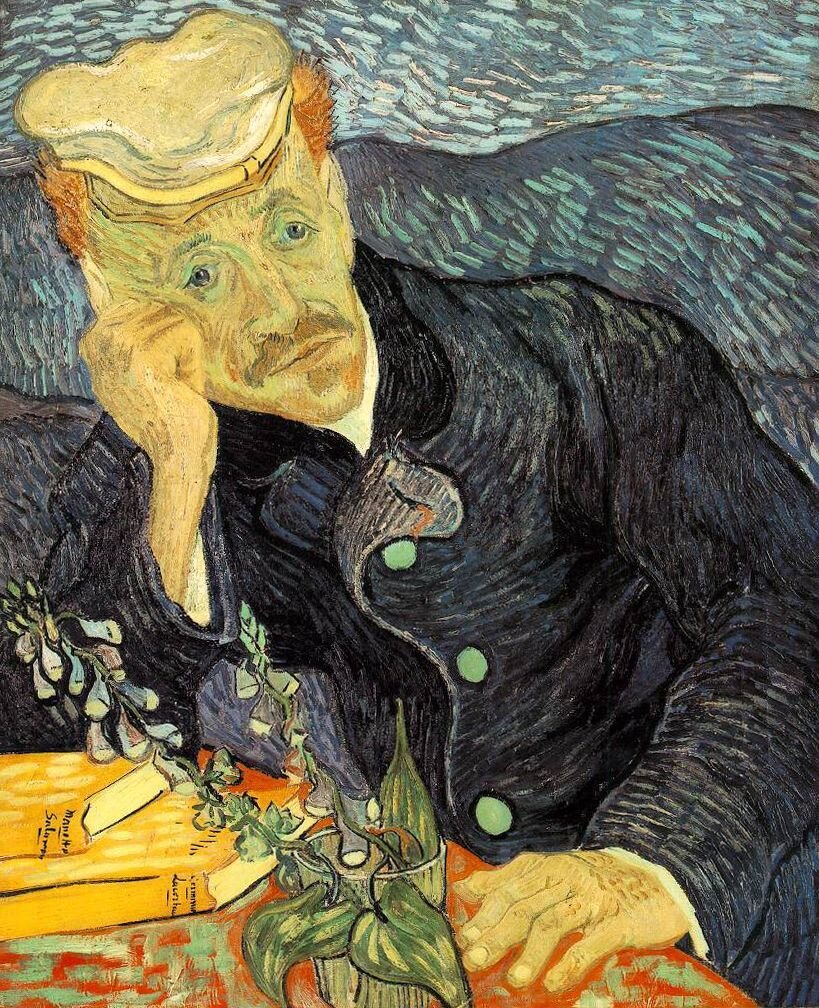

The Portrait of Dr. Gachet that we’re concerning ourselves with today is the first version-- the first of two similar, but by no means identical, portraits of the doctor. In both scenes, Van Gogh painted the good doctor resting at a red table in front of an abstracted blue background, supporting his head with his right fist and his elbow planted firmly on the table. He wears a blue jacket and a cream-colored cap, chilling here with a couple of bright yellow books, and in both canvases, he is accompanied by blooms of purple foxglove, the plant from which the substance digitalis is harvested-- a substance that was frequently used for the treatment of many ailments in the late 19th century, and one that Gachet probably prescribed to Vincent. (There are fascinating connections to Van Gogh’s digitalis use and his ability to perceive particular colors-- which I do mention in ArtCurious, the book, so please be sure to check that out for more really cool connections). This first version is, in my mind, the superior one, the better canvas, than the second, which is now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, but both were completed in the same period-- June of 1890, just one month before the artist’s untimely death. Part of the superiority is in the handling of paint and color here, to be sure-- but also in the doctor’s expression, a kind of sightless seeing, a vacancy that looks beyond us, the viewers, into the sadness of the world. And indeed, this seems to have been Vincent’s intention, writing to his frenemy, Paul Gauguin, that the doctor’s face represented the quote “the heartbroken expression of our time,” unquote. It is, in all likelihood, the final portrait ever painted by the great artist, and one that he had originally envisioned as a quote-unquote “modern” portrait, imbued with emotion and psychological meaning. And it delivers. You feel Gachet’s exhaustion, his sadness, his desperation, perhaps, when you look into his face. Or maybe it’s just a sensation of emptiness, that thousand-mile stare brought on by some existential crisis. Whatever it is, it’s a portrait that goes beyond a representation of the sitter itself, but one that may even reflect the artist’s own mindset. Indeed, Theo van Gogh originally mentioned that he felt Gachet resembled his own brother. It thus might not be a mistake that the final portrait bears more of a resemblance to the artist than it does to pictures of the real Paul Gachet.

We know from Van Gogh’s many letters to his brother that his connection to Gachet had begun to sour somewhat in late May and early June of 1890. To Theo, he wrote, quote, "I think that we must not count on Dr. Gachet at all. First of all, he is sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much, so that's that. Now when one blind man leads another blind man, don't they both fall into the ditch?” Nevertheless, the doctor continued to be an influence in the artist’s life, the subject of these final portraits, and one of the men who tended to Vincent at his deathbed. (Interesting tidbit-- the doctor, who was himself an aspiring artist, even went so far as to create a sketch of Van Gogh on said deathbed, a work he later translated into an etching). At Vincent van Gogh’s funeral, Gachet eulogized his patient, calling him a, quote, "honest man and a great artist... who had only two aims, art and humanity." unquote.

Coming up next: if you think the story of Vincent’s making of the Gachet portrait was interesting, wait until you hear about its record-breaking and mystery-making afterlife. Stay with us.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

The journey that the Portrait of Dr. Gachet took from this little-portrait-of-a-friend to a record-breaking superstar is a long, twisty, and interesting one (and so, too, are the travails of the second version, which I won’t go into today but might come up in a future episode). After Van Gogh’s 1890 death, many of his artworks fell into the hands of his sister-in-law, Johanna, Theo van Gogh’s wife and widow, as Theo followed his older brother to the grave only six months later. Jo van Gogh is another fascinating figure, and it’s entirely possible that I’ll cover more about her in a future episode, suffice to say that she was her brother-in-law’s artistic supporter, pushing his work in front of art collectors and critics long after the Van Gogh brothers’ passings. In the first decade of the 20th century, Johanna van Gogh first sold the Portrait of Dr. Gachet, which then changed hands a further two times, at least, before it was acquired in 1911 by Städel Galerie in Frankfurt, Germany. The story goes that the Städel’s art director was a forward-thinking man who was among the first in Germany to understand the artistic value of Van Gogh’s works, especially in the context of building up a collection of modern European artwork. Within this realm, Dr. Gachet gained some level of celebrity to the people of Frankfurt, who proudly considered the canvas as a citizen of their fair city. And thus it remained and everyone lived happily ever after.

Well, no. Unfortunately, such a blissful story ending isn’t in the cards for the Portrait of Dr. Gachet, YET, so we’ve gotta get through the dark years of the rise of Adolf Hitler and the second World War first. After Hitler’s appointment as German chancellor in 1933, he proclaimed a no-holds-barred cultural attack on any artwork that he considered quote-unquote “degenerate.” It’s a subject we’ve discussed before on ArtCurious-- be sure to go back to episode #54 on Otto Dix to recall the details of “degenerate art.” Concerned about the Portrait of Gachet and other sure-to-be-deemed-degenerate works, Städel officials hid the painting in a secret room within the museum, and it remained there, surviving two raids of unacceptable artwork by the Third Reich’s Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Alas, the third time was the charm for the Reich, and they located--and looted-- the painting in 1937. From here, the work bounced around between the agents of Nazi Party bigwig Hermann Goering and several art collectors, and during the exodus of many Europeans of Jewish descent to the United States for sanctuary, one of them--Siegfried Kramarsky, a German-born and philanthropist brought the Portrait of Dr. Gachet along with them to New York City.

The Kramarsky family maintained ownership-- or, given the iffy and complicated question of who gets to “own” looted art, perhaps we could say that the Kramarsky family claimed responsibility for the Portrait of Dr. Gachet for most of the remainder of the 20th century. They occasionally loaned the painting out for exhibition, and in the 1980s Siegfried Kramarsky’s heirs allowed the painting to be put on long-term loan at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was a great move altogether, because public interest in the artist had been steadily on the rise since the 1930s, and the Portrait of Dr. Gachet thus proved to be incredibly popular. It was also important in presenting an image of a close friend and confidante of Van Gogh-- a powerful reminder of the artist’s connection to others and a counterpoint to that traditional narrative of Van Gogh-as-tortured genius.

And it is this moment in history where the iron strikes hot. Seeing the popularity of Van Gogh’s works--as well as a booming art market-- led the Kramarsky family to the decision to sell their prized possession, and they consigned it to the famed auction house, Christie’s, in 1990. By all accounts, this was a good move, and both the family and Christie’s had every reason to expect a nice return. As we know, Van Gogh was popular the world over by now, but by the late 1980s, one particular sector was particularly enthusiastic about collecting Van Gogh works: the Japanese elite. There appears to have been a rush on Van Gogh due to the artist’s known interest in Japanese woodblock prints, which inspired some of his artworks during the final year of his life. Van Gogh wasn’t the only artist at this time who was obsessed with what was then called “japonisme”-- many artists were, and if you listen back to episode #68 about Katsushika Ōi and her father, the great printmaker Hokusai, then you’ll recall the fad among late 19th-century Europeans for all things Japanese. But that double interest-- in Van Gogh, and in Van Gogh’s adoration of japonisme-- made his deliciously tempting to Japanese art collectors. Just three years prior, in 1987, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers had sold for approximately $37.9 million at Christie’s in London to a Japanese insurance titan-- and further domestic sales of Van Gogh paintings were also faring very well. And the strength, at that time, of the Japanese currency, the yen, certainly couldn’t hurt. But neither Christie’s nor the Kramarsky family expected the results of the auction on the evening of May 15, 1990.

Based on the popularity of Van Gogh’s works at the time, Christie’s valued the Portrait of Dr. Gachet at somewhere between $40 to $50 million. Not a small chunk of change in the early ‘90s. And during the auction for the lot itself, things seemed to be going well-- bidders began to bid, and the going among began to rise. When the auctioneer called out a price of $50 million--which was not only the upper limit at which the auction house had valued the work of art, but was also then the world record for the highest amount ever spent at an art auction, the audience began to applaud, understanding that they were witnessing an historic moment. And yet the bidding didn’t stop, with the price rising higher and higher until one secretive buyer remained, and the hammer dropped for a new world record: $82.5 million after fees, or an inflated price of about $161.4 million in today’s dollars.

Per typical auction-house conservatism, the buyer of Portrait of Dr. Gachet wasn’t immediately revealed, but it didn’t stay hidden for too long. It soon became public knowledge that Ryoei Saito, an honorary chairman of the Daishowa Paper Manufacturing Co, now Nippon Paper Industries, had purchased it. And Saito was on a roll with his interest in acquiring Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art. Just two days after he bought the Gachet, he dropped another $78.1 million for a work by Pierre-Auguste Renoir at auction rival Sotheby’s. But his Van Gogh--that world record-setter-- was especially beloved by him. He guarded it jealously, not lending it to exhibition and only showed it to the closest of confidantes and business associates. It was truly a reversal for the painting, which had gone from being publicly adored at the Met to privately held and seen by only an extremely elite few. And this here is the twist in this tale-- making this unexpected story even more surprising-- because the Portrait of Dr. Gachet hasn’t been seen in public at all since that sale in the Spring of 1990.

In the past thirty years, many have made it their mission to try and locate the Portrait of Dr. Gachet, because knowledge of the work's whereabouts became especially scarce after the death of owner Ryoei Saito in 1996. Even Saito’s own son declared that he had never seen the work, nor did he know where it was located. And after the Metropolitan Museum of Art attempted to secure the loan of the portrait for a late ‘90s art exhibition, things became more worrisome. And here was their concern: in the early 1990s, Ryoei Saito was publicly angered by the millions of dollars payable in taxes for both the Van Gogh and the Renoir he bought in 1990. Somewhat off-handedly, Saito then claimed that he intended to have these paintings cremated alongside him after his death, so that his heirs wouldn’t be saddled with this taxation burden. Surely it was a joke, right? I mean… right? Suddenly, there was this intense fear that one of Van Gogh’s most meaningful works in the last weeks of his life was just gone. And with that fear, a worldwide search--20 years now in process-- was begun.

Much of the searching for the Portrait of Dr. Gachet has been done at the hands of the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, the institution that had, for a period at the beginning of the 20th century, claimed Gachet as one of their star attractions. And just last year, 2019, the museum put out a five-part podcast series called Finding Van Gogh, in collaboration with journalist Johannes Nichelmann, that details the ongoing search for the portrait. (definitely check out this podcast if you want to know all the nitty-gritty details about both the portrait and the ongoing search.) Nichelmann did extensive research, spoke to all the right people, and yet he was unable to get the explicit answers he sought. But he did receive confirmation, at least to a degree, about the painting’s path after Ryoei Saito’s death-- and thankfully, that path did not go straight to the crematorium. After Saito’s death, it appears that his estate was handled by a Japanese bank-- and the estate included, among many other assets, the Van Gogh and the Renoir. Secretively in the late 1990s, Sotheby’s was brought aboard to broker the sale of the Portrait of Dr. Gachet to an anonymous buyer-- one who has been theorized, all these years later, as one Wolfgang Flöttl, an uber-rich Austrian investment banker. But, Nichelmann was repeatedly told, Flöttl no longer had the Portrait of Dr. Gachet. It was now in the hands of someone else. Another mysterious and secretive collector. Again, and again, Nichelmann heard the same answer: “I know someone who knows where it is. But I can’t tell you anything.” Switzerland keeps popping up as a little hint, which makes good sense. As we discussed in our last episode on Mark Rothko and the so-called “Bouvier Affair,” Switzerland’s status as a tax haven is a boon for collectors of the world’s priciest goods, including works of art. And another art world rumor swirls that the portrait’s current owners are the family of a now-deceased Italian super-collector, one who already had several other major Van Gogh paintings at his fingertips. But we just don’t know for sure, nor do we know why the last few owners of the Gachet painting choose to be so secretive about it. But here’s my best guess: we haven’t seen the last of the Portrait of Dr. Gachet. For me, it is now running a parallel life with that of Salvator Mundi, as both works have been out of the public eye since their respective very prominent auctions. We might not know where they are right now, but they are probably safe--and odds are that, either through another splashy sale or a surprise exhibition loan, we will see Dr. Gachet’s face, as lovingly delineated by Vincent van Gogh, once again.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal, with additional writing and research help by Jordan McDonough and Joce Mallin. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, and our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com. Our audio production services are provided by Kaboonki, the silliest name in superb podcasts and video. Let them help you too at kaboonki.com. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator. For more details about our show, including the image mentioned in this episode today, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod.

Check back with us in two weeks when we explore the unexpected, slightly odd, and strangely wonderful in the most expensive works ever sold at auction.