Episode #65: The Coolest Artists You Don't Know: Edmonia Lewis (Season 7, Episode 5)

ARTCURIOUS: Stories of the Unexpected, Slightly Odd, and Strangely Wonderful in Art History is available now from Penguin Books!

For most Americans, there’s a list of arts that they might be able to rattle off if pressed to name them off the top of their heads. Picasso. Michelangelo. Leonardo da Vinci. Name recognition does go a long way, but such lists also highlight what many of us don’t know-- a huge treasure trove of talented artists from decades or centuries past that might not be household names, but still have created incredible additions to the story of art. It’s not a surprise that many of these individuals represent the more diverse side of things, too-- women, people of color, different spheres of the social or sexual spectrum.

This season on the ArtCurious podcast, we’re covering the coolest artists you don’t know. This week: Edmonia Lewis.

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts!

SPONSORS

The Great Courses Plus: Enjoy a free trial of The Great Courses Plus's entire library

MOVA Globes: use code "ARTCURIOUS" for 10% off your order

Episode Credits

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Logo by Dave Rainey. Social media assistance by Emily Crockett. Additional writing and research by Adria Gunter.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits

"Cad Goddeau" by Nest is licensed under BY-NC-ND 2.0 UK; "Gnossienne 4" by Chad Crouch is licensed under BY-NC 3.0 International; "Five" by Marcel Pequel is licensed under BY-NC-SA 3.0 US; "この気持ちはなんて言うんですか" by Julie Maxwell is licensed under BY-ND 4.0; Based on a work at http://www.juliemaxwell.com; "Seven" by Dexter Britain is licensed under BY-NC-SA 4.0; Based on a work at http://www.dexterbritain.com "glonn" by Stephan Siebert is licensed under BY-NC-ND 4.0. Ads: "Free Time" by Mela is licensed under BY-SA 4.0 (Mova Globes)

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Links and further resources

Alice George, "Sculptor Edmonia Lewis shattered gender and race expectations in 19th-century America." Smithsonian Magazine. Aug. 22, 2019.

Penelope Green, "Overlooked No More: Edmonia Lewis, Sculptor of Worldwide Acclaim," The New York Times, June 25, 2018.

Talia Lavin, The Decades-Long Quest to Find and Honor Edmonia Lewis's Grave. Hyperallergic, March 28, 2018. Article.

Susanna W. Gold, "The Death of Cleopatra / The Birth of Freedom: Edmonia Lewis at the New World's Fair," Biography: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly, Volume 35, Number 2 (Spring 2012) pp. 318-341.

Marilyn Richardson, "Edmonia Lewis's The Death of Cleopatra." International Review of African American Art, 12, no. 2 (1995): pages 36–52.

For image details, please click on the image itself:

Episode Transcript

How is it that some things can become so, so popular and then fade from memory so quickly? Trends come and go, and fads are usually short-lived, sure, so that’s not a huge mystery, but how can a highly-lauded and celebrated public figure, for example, move from acclaim to obscurity with hardly a second thought? In our own age and with the internet at the ready, our footprints last a bit longer, but over 150 years ago, there lived an artist so lauded, so celebrated, that people would visit her art studio from the world over, but by the beginning of the 20th century, few remembered her name. And luckily for us, that is no longer the case.

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, crazier, or more fun than you can imagine. In season seven, we’re uncovering the coolest artists you don’t know, and today, it’s the story of Edmonia Lewis, who reached huge heights and international acclaim during her lifetime and laid claim to a number of distinguishing characteristics: self-made woman, sought-after American expat sculptor, and one of the first women of African-American and Native-American heritage to make it to the big time. This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

Mary Edmonia Lewis is believed to have been born on July 4, 1844, though no one knows exactly for sure, and the years that have been bandied about range from 1840 through 1844. What is known, though, is that she was born free in the town of Greenbush, New York, a black woman not born into an enslaved family in the U.S. in the years preceding the Civil War. Her father, Samuel Lewis, was of African and Haitian descent, while her mother, Catherine, was of African-American and Native-American descent, with family stemming from either the Chippewa tribe or a sub-tribe related to the Ojibwe from Canada’s First Nations. This mixed-heritage was something of which Lewis herself was hugely proud, and something that would invariably come to play in her artwork, which we’ll get to in a moment. She was especially close to her mother’s side of the family, who essentially raised her after she was orphaned at either the age of five or nine-- again, no one is quite sure of the exact timing when it comes to Edmonia Lewis here. Her mother’s relatives were semi-nomadic, and she engaged with them in selling Native American trinkets, moccasin-sewing, and enjoying all the freedoms of living so close to nature. You can really get a sense of Edmonia’s love of the world around her from her writings later in life. One of her most famous sayings was, quote, “There is nothing so beautiful as the free forest. To catch a fish when you are hungry, cut the boughs of a tree, make a fire to roast it, and eat it in the open air, is the greatest of all luxuries. Unquote.” She then, equally famously, continued her statement by saying, quote, “ I would not stay a week pent up in cities, if it were not for my passion for art." Unquote

1859 was a big year for Edmonia Lewis-- her older brother, Samuel, had moved West previously with hopes of prospecting gold, and with his financial assistance, Edmonia Lewis moved to Ohio in 1859 to attend Oberlin College with the intention of studying art there. Although Oberlin accepted both women and African-American students in a time where accepting one or the other, let alone both, was actually pretty rare for U.S. educational institutions, this didn’t mean that Lewis had a great time there. In fact, Lewis’s experiences at Oberlin were fraught with racism. In that way, it was not unlike Henry Ossawa Tanner’s experiences at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, as we discussed in the second episode of our current season. But it was very different from Tanner’s in its severity. In 1862, three years after the beginning of her tenure at Oberlin, something strange happened. Lewis, ostensibly hanging out with friends before an afternoon sledding trip, served two female classmates some spiced wine. A nice thing to do on a cold day, right? Well, that may have been the intention, but the outcome wasn’t good: Edmonia Lewis’s two classmates became severely ill soon after. Though the women recovered from their sicknesses, and though doctors found no evidence of foul play, Lewis was soon caught up in a firestorm of scandal and rumor. Lewis, some said, had attempted to poison her classmates. The town of Oberlin didn’t take this well. And again, though there was nothing to point to anything concrete, that didn’t matter, and some tried to take the matter into their own hands. One evening, while walking home at night on her own, Edmonia Lewis was attacked, dragged into a nearby field, and beaten nearly to death. After her practically lifeless body was found, Lewis was arrested for the assumed poisoning of her two friends. Thank goodness this story has a happy ending, or at least a happy-ish. Lewis’s case was managed by the only practicing African-American lawyer in town, and he led her to an acquittal, even though most of the so-called witnesses testified against Lewis.

Not that the rest of her residency in Ohio went smoothly, as you can imagine. She still experienced quite a significant amount of racial prejudice post-trial, and was even accused of stealing art supplies from her art department. Again, no evidence came to light to support this, but the damage was still done. She was asked to leave Oberlin right before the start of her last term, unable to register in her final courses which meant that she could never graduate. It was after these turbulent years that she decided to rightfully put Ohio in the past and thus she left and relocated to Boston.

Art was at the top of the list for Edmonia Lewis in Boston, and thankfully she was able to make some worthwhile connections that made her recent relocation a real boon. With guidance and support from several abolitionists, as well as continued training under self-taught sculptor Edward Brackett, Lewis honed in artistic skills and managed to re-establish herself in a new, more welcoming environment. This time, she began to focus on one thing in particular: sculpture. Edward Brackett’s specialty was marble portrait busts, a bust being an image of a person from the chest up. And this rubbed off on Edmonia Lewis. Even though Brackett and Lewis eventually had a falling out, Brackett’s tutelage directly influenced his student’s artistic output and ability, and it went well. By 1864, she had made her first sale-- a sculpture of a woman’s hand, which she sold for $8; later that year, she enjoyed her first solo art exhibition, which was well-received. And at that point, things started moving pretty fast for her. She garnered increasingly more fame and attention throughout Boston and soon beyond, a fame she used to her personal advantage to reject the narrative previously assigned to her-- that she was a victim, the recipient of awful abuse and a survivor of a near-death experience brought on by prejudice, racism, and possible misunderstanding. Instead, she used the opportunity to craft the telling of her own life story. The press, in particular, was intrigued by her fantastical stories about her upbringing. As many would do in the same position, Lewis tended to emphasize and/or tweak certain aspects of her background to different publications and audiences, depending on what she was attempting to promote or sell. I mean, it seemed like a good idea at a time, but eventually this would end up causing modern-day art historians and biographers a whole lotta trouble as they’ve tried to sift between fact and fiction. Furthermore, Lewis’ mixed racial identity, as well as her gender, were both heavily covered by the press, for a woman of color pursuing a profession in the arts was a novelty in the U.S. during this time period, to say the very least. And then, top it all off with the fact that Lewis chose sculpture--let long considered a rather masculine form of artmaking due to the supposed strength and power needed to both wield sculpting tools and to manage the hard materials typically used, like marble, Edmonia’s go-to? Well. That was a lot of excitement to report upon, and so the press, too, began concocting their own versions of Lewis’s life story. For example, one widely circulated account of how she became a sculptor described her as, quote, “overwhelmed,” unquote, by the sight of a statue of Benjamin Franklin in Boston. At that moment, Lewis--supposedly lacking a sophisticated vocabulary to describe her understanding of what a sculpture was, reportedly cried, quote, “Oh, how I would love to make a man in stone!” Unquote. Narratives like these painted her as a kind of uneducated, rough-around-the-edges creator that audiences, especially white audiences, loved. It was almost a kind of rags-to-riches story-- look at the artist now, who not only could indeed “make a man in stone,” but also had the right knowledge and training to make it big. And in some ways, this myth-making suited Edmonia Lewis just fine, because it allowed her to keep her actual self, and her actual life, more of a mystery.

With such enthusiasm and press coverage of her life and works, Edmonia Lewis was able to save up enough cash based on her commissions and sales that she was able to undertake the next step in her career: a big relocation. In 1865, Lewis left Boston for Europe, joining a burgeoning population of American artists living and working abroad, as we mentioned in our previous episode on Tanner. Unlike Tanner, though, she opted to give Paris a pass and, like Angelica Kauffman, found inspiration instead in Rome. And she certainly wasn’t alone. In fact, something rather wonderful was happening in Rome at this time-- it was a gathering place for a group of American women sculptors, expatriates all, who were working together and supporting one another’s endeavors. The group included among them such artists as Harriet Hosmer, Emma Stebbins, and Margaret Foley. And it was Harriet Hosmer who urged Lewis to settle in Rome, arranging a studio rental near the Piazza Barberini, a place which, most auspiciously, was said to have been the former studio of the 18th-century Italian sculptor Antonio Canova. And here, Lewis thrived. It certainly didn’t hurt to work in such proximity to the kinds of things that made Rome, in its long artistic history and tradition, such a hot spot for sculpture-- things like access to the finest white marble in the world, like the famed Carrara marble, and highly-trained Italian stone carvers. At the same time, though, Edmonia Lewis was nothing if not an example of the independent American spirit, all do-it-yourself and pull-up-by-the-bootstraps mentality. Unlike most sculptors of her generation, Lewis rarely employed stone carvers to assist her, completing her works with little to no assistance. It was one of those things that immediately set her apart in a field so chock-full of talent. The other thing was Lewis’s care in choosing her subject matter for her sculptures. She paid critical attention to what was happening around her, and strategized smartly so that her works would appeal to the wants and needs of certain patrons. Consider, for example, the U.S. during the tail end of the Civil War, a period just prior to Lewis’s departure for Europe. As art history professor and author Kirsten Pai Buick writes about Lewis, quote, “During abolitionism, she found reciprocal interests and common interests with anti-slavery advocates,” unquote, relationships which thus prompted her to carve marble busts of newly freed African-Americans and the abolitionists who worked so hard to assist them. Similarly, after her move to Europe and the abolition of slavery in the U.S., transitioned out of African-American and abolitionist portrayals and, like Henry Ossawa Tanner would later do in Paris, she transitioned instead towards creating religious sculptures, something she would have clearly witnessed in a Catholic country like Italy. She was aware of pop culture trends, too, and smartly worked within those realms. Take, for example, two of her most well-known works of art, marble busts of the star-crossed Native American lovers Hiawatha and Minnehaha. Both works, created in 1868, paid homage to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, which was hugely popular during this period. (And sure, it didn’t hurt at all that such works were also a little nod to her own Native American heritage, which must have added cachet to her depictions). By no means was the artist’s machinations an oddity-- not then, and not now, in today’s contemporary field, either. But Edmonia Lewis not only catered to the wishes of her audiences, she also became hot stuff during her own lifetime, just as Henry Tanner would do. Think of it: one of the greatest artists of her time, a sculptor receiving international commissions and acclaim, and she was an American woman of mixed heritage living and working abroad. If Edmonia Lewis isn’t one of the greatest success stories in art, I don’t know who is.

The acclaim and coverage of Edmonia Lewis’s life and work kept on coming, and her success was international news. Take, for example, an article cited by historian Eleanor Tufts, who found a 1873 declaration in the New Orleans Picayune that, quote, "Edmonia Lewis had snared two 50,000-dollar commissions." Unquote. In today’s cash, that’s the equivalent of two commissions valued at more than one million dollars each. No wonder that she not only enjoyed solo exhibitions of her work in major cities like Chicago and Rome, but that her art studio even became a highly-popular tourist destination.

Perhaps the most fascinating story about Edmonia Lewis isn’t about her, per se, but about the life of her most famous work of art, a story that reveals the rise, fall, and rise again of Edmonia Lewis’s popularity, influence, and acceptance. But first, a little background. With her international acclaim and appeal, it made sense that her works would be requested for the biggest events of her day. And one of the biggest was the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, held in Philadelphia that year. Now, if this sounds familiar to you, that’s because we discussed the Centennial Exhibition way back in Season 5 of ArtCurious, because it was the same “World’s Fair”-type celebration of the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence at which Thomas Eakins first revealed his masterpiece, The Gross Clinic. For her participation at the exhibition, Edmonia Lewis went all out. No portrait busts, no small figures. Nope. This was huge, literally. For this event, she sculpted a monumental, full-body image of Cleopatra, seated on her throne, in the last moments of her life after allowing herself to be bitten by a poisonous snake. The Death of Cleopatra weighed more than 3000 and was a major sight to behold, quickly becoming one of the most popular works of art in the Centennial Exhibition due to its combination of Cleopatra’s sensual beauty and the fact that her sculptor chose to memorialize the end of her life, rather than another moment from Cleopatra’s much-lauded life. But of course this was deliberate. Remember: Edmonia Lewis knew what she was doing, and she was very smart with her intentions for her work. In her article “The death of Cleopatra / the birth of freedom: Edmonia Lewis at the new world's fair,” Susannah Gold traces the link between the ideals of freedom and independence that the Centennial Exhibition celebrated, and Lewis’s choice of Cleopatra as her subject to be shown in a country whose track record with freedoms and independence had been directed only at certain peoples. But as a woman of partial African-American heritage, she was careful not to allude directly to the emancipation of slaves, nor to any possibly touchy subjects that might infuriate a still-seething, post-Civil War country. But, as Gold points out, the knowledge that Cleopatra, though not typically portrayed as a black African, was indeed from the continent of Africa-- the connection between what Gold calls the “potential expectation of Cleopatra’s blackness” and Edmonia’s own heritage and experiences of racism was the ever-present subtext. Cleopatra had become a symbol of Africa’s power, of its beauty, a reminder of the glories of its historical figures and the importance of its present descendants. And that was a big statement. But it was also a potential firestorm if made explicit. So Lewis sculpted her game-changing sculpture in gorgeously pure white marble, effectively and almost literally whitewashing Cleopatra from a racial perspective.

Now, all of this is enough to make The Death of Cleopatra stand out in Lewis’s career. But what happened next to this sculpture is crazy, and definitely a story for the art history books. After the Centennial Exhibition, the intention was that such a stunning work would get sold off, either to an art collector or to a museum, but this didn’t pan out, for whatever reason. Certainly the neoclassical sculpture style that Lewis and others were working in would slowly lose popularity, but regardless, the outcome was the same: The Death of Cleopatra remained unsold, and the work was too huge to ship to Europe. It had to remain in America. So, Lewis placed the work in storage before agreeing to exhibit it one more time, two years later, Cleopatra was shown stateside one more time, in an exhibition in Chicago. It was finally at this point that the work of art was officially sold. It was bought by a man known as “Blind John” Condon, a saloon owner in Chicago. Condon’s side hustle was a horse racing track in nearby Forest Park, Illinois, where his favorite mare, named Cleopatra, frequently ran. When Cleopatra the horse passed away, Condon was so distraught that he refashioned Lewis’s sculpture as her headstone, with the stipulation that neither it, nor the horse’s grave, be moved from its site. But as the horse track changed hands--and morphed from a golf course to Navy base to post office-- the de facto owners of Cleopatra ignored Condon’s stipulation and moved the giant marble sculpture to a scrap yard, where it sat, ignored and unkempt. The Death of Cleopatra was all but forgotten. But that wasn’t the end of the story. In the late 1980s, a retired fireman--and Boy Scout troop leader-- “found” the work at the scrap yard in Forest Park and declared it a perfect fit for a Scout service or renovation project. Together the Scouts and troop leaders glued and painted Cleo and then presented her to the Historical Society of Forest Park, not knowing of its maker or the meaning of the artwork. But some had an inkling of its importance. Historical Society director Frank Orland, through a long process of research driven by utter curiosity, sherlocked his way into a belief that Edmonia Lewis had created the work, and his sleuthing tipped off Marilyn Richardson, an independent curator and Lewis scholar. Orland became sure that he was sitting on the long-lost, forgotten Edmonia Lewis masterpiece. Richardson was hopeful but wary, but she did what she felt was necessary: she traveled to Forest Park and joined Frank Orland to view this purported Lewis sculpture. And it was there, standing amidst discarded Christmas decorations, half-empty paint cans, and other detritus in Forest Park Historical Society’s storage facility, that Marilyn Richardson confirmed the piece’s attribution. Frank Orland’s hunch was right. And The Death of Cleopatra, after more than 100 years, finally received the honor it deserved. Today, the work is a star attraction at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and I can’t imagine a better place for one of the most fascinating and important works by a 19th century American sculptor. But I still think it is still kinda cool that it was a horse’s monument for a while.

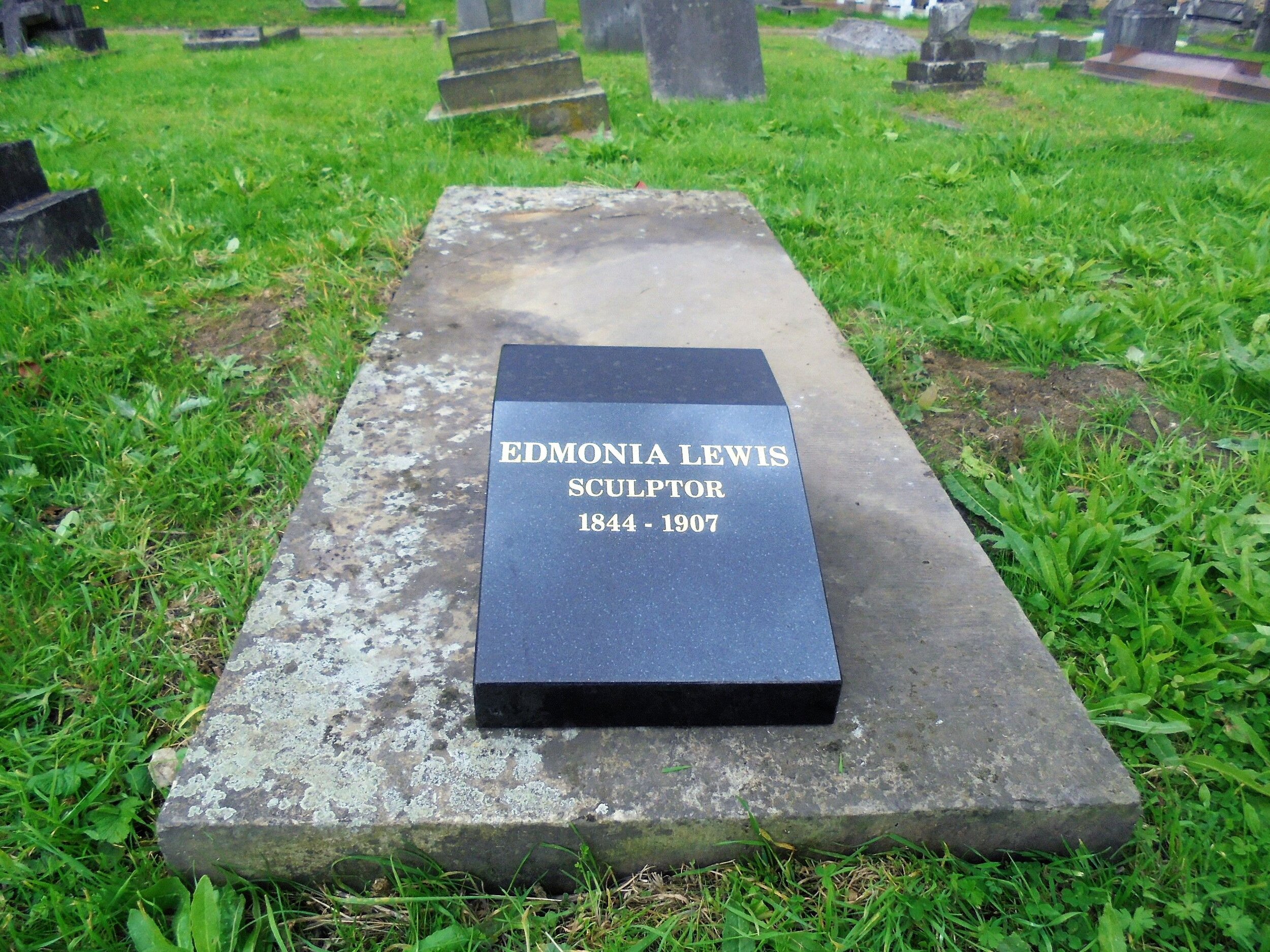

Many have noted that the story of the loss and rediscovery of The Death of Cleopatra strangely mirrors the events of Edmonia Lewis’s own life. By the late 1870s, Lewis was still creating highly sought-after portraits for the likes of former president Ulysses S. Grant, and her studio was still a tourist attraction. But, as I mentioned previously, the excitement over neoclassical artwork was really out of favor by the time that the 1880s rolled around, and Lewis’s clientele began to diminish. By the turn of the century, she had produced mainly religious sculpture for Italian Catholic churches and little else. At that point, she made a change and moved, in 1901, to London. And this is where much of the trail went cold-- much of what transpired in the final years of her life is a mystery to us today. Like The Death of Cleopatra, it seemed like Edmonia Lewis was disappearing from art history, even in the midst of her own time. She had fallen into obscurity so much that, until relatively recently, the year of her death--let alone the exact date of it, or the location of her death--was only guessed at. Some thought she died in Rome, some that she was buried in an unmarked grave in California’s Bay Area, and even still, a magazine published in 1909 noted that she was still alive and living in Rome. No one really knew what happened to Edmonia Lewis. But thankfully, as interest in female artists started picking up momentum in the 1970s and beyond, a new understanding and reassessment of Edmonia Lewis as an artist took hold. Thanks to the diligence of scholars like Marilyn Richardson, Kirsten Pai Buick, and others, she has rightfully reemerged into the public sphere-- and some of those mysteries are beginning to firm up, too. Only in 2017 did a coalition of researchers finally pin down the date of her death-- September 17, 1907-- as well as answer that long-asked question: where did she end up? Edmonia Lewis, famed sculptor of her day, died in London. She was buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery of St. Mary's in London, and a brand-new, sparkling headstone now highlights her once-forgotten grave.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal, with additional writing and research help by Adria Gunter. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com, and social media help is by Emily Crockett and Caroline Haller. Our production and editorial services are provided by Kaboonki. Audio production services are provided by Kaboonki, the silliest name in superb podcasts and video. Let them help you too at kaboonki.com. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator. We’re a fully independent podcast, and we rely on sponsors and donations to keep us going, so if you enjoy this show and have the means, please consider giving $10 to help this show, and thank you for your kindness. And if you don’t have money to give, that’s okay! You can help our show as well by leaving a five-star review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen-- believe me, it makes a huge difference and helps new listeners tune in. For more details about our show, including the image mentioned in this episode today, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod.

Check back in two weeks as we continue to explore the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in art history.