Episode #16: The Muse

Sometimes when I am looking at a particularly fascinating work of art, I find myself overwhelmed with awe-- for the creative act itself and the technical prowess that was needed to bring it to fruition. I’ve often had those moments where I have thought to myself, “Wow. How did this all come about? What is the inspiration behind this piece?” And any conversation about inspiration in the arts inevitably brings up a discussion about muses. This episode looks at the relationship--and occasional romance-- between artists and their muses, with a particular emphasis on one woman whose connection to two brothers illustrates this exchange in a compelling way.

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts!

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Episode Transcript

Sometimes when I am looking at a particularly fascinating work of art, I find myself overwhelmed with awe-- for the creative act itself and the technical prowess that was needed to bring it to fruition. I’ve often had those moments where I have thought to myself, “Wow. How did this all come about? What is the inspiration behind this piece?” And admittedly, that’s the whole concept behind this podcast-- learning the fun and captivating stories in art history. The tale about the invention of painting is an interesting one in and of itself. But I’m not talking about how painting was actually probably invented, wherein our ancient ancestors palmed pigment directly onto their cave walls. No, this one is much more fanciful. According to a legend spun by the Roman author Pliny the Elder in the first century, the very first portrait of a human being ever created was by a Corinthian woman in 600 BC. This woman, sometimes referred to as Cora or simply the Corinthian Maid, was deeply in love with her soldier boyfriend, who was due to leave town the following day. Late that night at the maid’s home, the young man fell asleep, and as the maid gazed adoringly at her beloved, she noticed his shadow projected on the wall behind him by the flickering candlelight. With a flash of inspiration, she delicately traced his profile directly onto that wall, capturing his visage so that she could remember him and their romance in his absence. Painting-- or portraiture, really-- had been created, for the very first time.

Pliny’s sentimental legend has been a popular one throughout the last two thousand years, becoming particularly fashionable during the late eighteenth century when all things Greco-Roman were deemed the height of sophistication. And the romantic element certainly only prolonged its popularity. But what I love most about this story isn't the love story, though it is certainly swoon-worthy. It's the fact that the subject--or muse, actually-- is a man, and that the artist creator? The Corinthian maid--a woman.

Sometimes people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But sometimes, the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, crazier, or more fun than you can imagine. Art History is full of murder, intrigue, feisty women, rebellious men, crime, insanity, and so much more. And today, we are going to look at the relationship--and occasional romance-- between artists and their muses, with a particular emphasis on one woman whose connection to two brothers illustrates this exchange in a compelling way. Exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History, this is the ArtCurious Podcast. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

Like the story of the origin of painting, the concept of the muse stems from the ancient world. Muses come from Greek Mythology, where they were hailed as the nine inspirational goddesses of the arts. Each of the original nine muses has a specific forte-- music, love poetry, history (Strangely enough, the original nine muses covered about three different types of poetry amongst them, but none covered the visual arts, so… go figure.) Later, the muses became part of the Roman pantheon of gods and goddesses, so they became worshiped in their own right as celestial figures whom you could contact in times of creative need. But like so many deities or holy figures, eventually they are brought down to earth and re-purposed for secular needs. After the fall of the Roman empire and the adoption of Christianity throughout the Western world, the term “muse” no longer had the same spiritual connotation. Instead, it transformed into a phrase that could be used by anyone claiming a specific person as an inspiration or an artistic influence. But one thing that did seem to stick from ancient times is the identification of the muse as a woman. Which then, of course, means that the creative type was a man. Once a goddess, now a lowly mortal who can subtly influence the male genius. Oh, how the mighty have fallen.

It seems like artists and creators could really go in two directions with their adoption of a muse. The first is an indirect approach, wherein the artist chooses an unattainable woman upon whom he can project his love and fantasies. In turn, this unattainable woman inspires the creation of the probably semi-tortured artist’s masterpieces. The epitome of this relationship is that of the early Italian Renaissance poet, Petrarch, and his love, Laura. In the 1320s, Petrarch, who had previously hoped to become a priest, caught sight of a woman named Laura in a church in Avignon, France. We really know next-to-nothing about the historical Laura, except that she was beautiful, with light hair and a dignified bearing. According to his book, Secretum, or The Secret, Petrarch did meet Laura officially, but she rejected his advances because she was already married. However, everyone who has ever listened to a hair-band ballad knows that the best works of art come from heartbreak, so Petrarch’s poems blossomed in spite of his lovesick despair-- or, more accurately, because of it. Same goes for Petrarch's precursor, Dante Alighieri, and his undying love for his muse, Beatrice.

Some pundits and philosophers who have examined the special relationship between the muse and the artist have stated that this distance is actually what makes a true creative relationship. Indeed, Germaine Greer, that stalwart of second-wave feminism, wrote in 2008 that QUOTE “Physical congress with one's muse is hardly possible, because her role is to penetrate the mind rather than to have her body penetrated.” And Greer goes further to say that there is actually a gender reversal going on in the artist and muse roles-- because it is the man who brings forth the creation from within himself after being germinated by the muse, so to speak. But as much as Greer wants us to think otherwise, there is a secondary direction that the artist-slash-muse relationship can, and often does, take. And once we move past the courtly love epochs of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, this type of relationship became especially popular. Because of the intimate nature of the act of creating anything, whether it be visual art, music, an epic poem or the like, the muse tended to be someone with whom the artist could closely connect. This meant that for some artists, his muse was a woman already of utmost importance in his life: a crush, a lover, a wife, or mistress. There, it seemed, was a natural gravitation towards a romantic or at least an erotic, if not always sexual, relationship. Jumping into the 20th century, we find an artist who epitomizes the artist dependent on a muse, and who had a variety of them throughout his long lifetime-- a couple of whom he ended up marrying. This is Pablo Picasso, that great artist and consummate womanizer. Picasso’s view of women certainly isn't a kind one. He very famously once said, quote, “There are only two kinds of women, goddesses and doormats.” And he supposedly said this to one of his mistresses! So a person who was kind to and about women, Picasso most definitely was not. But it’s almost impossible not to take his wives and mistresses into account when looking at much of his creative output. Both of his wives--Olga Khoklova and Jacqueline Roque-- as well as some of his more famous mistresses, including Fernande Olivier, Dora Maar, and Francoise Gilot--inspired him throughout his lifetime, beginning with some of his earliest cubist works and moving towards the last decade of his life. As Sotheby’s Scholar Georgina Gold noted, quote, “Picasso was incredibly passionate and the way he orchestrated the portraits of the women in his life really expressed his feelings at the time. It's fascinating to look at how each image of the women in his life and how he was representing them, and how it reflects his career and personal life. It's all intertwined." Though each of these women played an important role in Picasso’s artistic development, one muse tends to stand higher than the rest: and that is one of his youngest mistresses, Marie-Therese Walter, who began a relationship with the master when she was just seventeen years old and he was 45. At the time-- the late 1920s-- he was also still married and living with his first wife, Olga, but together he and Walter carried on a secret affair for nearly a decade until Picasso left Walter in favor of a dalliance with Dora Maar. But during the course of their relationship, Marie-Therese Walter was the inspiration for the blond, bright, and sunny women in some of his most acclaimed works from the 1920s and 1930s, such as The Dream and Girl Before a Mirror, images of which you can see on the ArtCurious website. So for Picasso, the idea of sex and romance wasn't separate from the art of creation: it was integral.

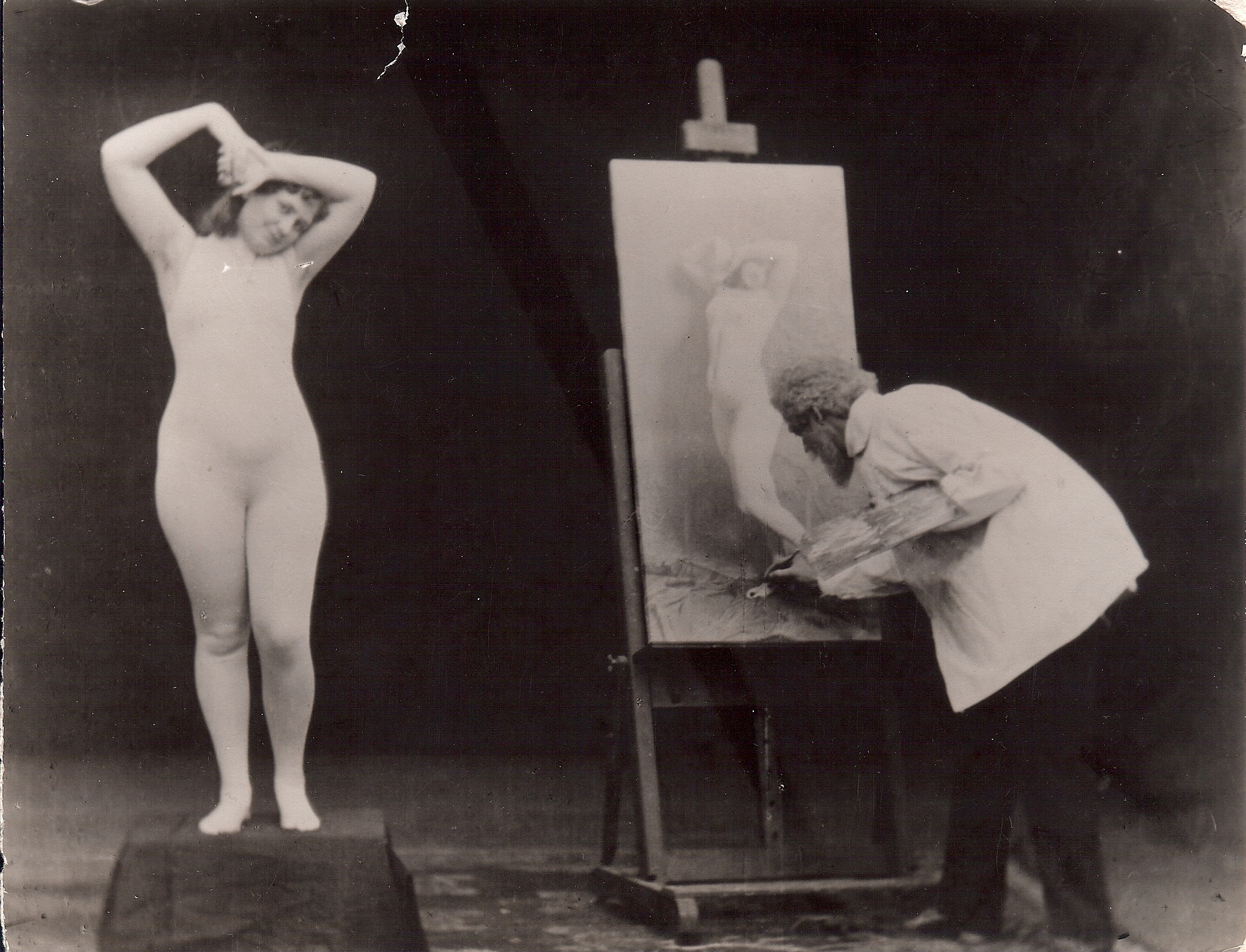

We could probably spend an entire hour of this show just rattling off the names and relationships between world-famous artists and their muses. But the one thing that tends to be pretty standard is that the muses are typically female, and those creative geniuses are men. We’ve talked a bit before in previous episodes of this show about the many difficulties and challenges that faced women who pursued careers in the visual arts prior to the 20th century--not the least of which includes the strict banning of female artists from drawing from the nude model. So, it’s necessary to remember that women might not have had the chances to develop their own muses in the same may as their male counterparts. That isn’t to say that there weren’t some great women who turned the tables on these gender roles and found their own muses- some of whom just happened to be men.

One particular artist had a unique artist slash muse relationship, acting as each throughout the course of her life-- and developing her own muses, plural, along the way, too. This is Berthe Morisot, the French painter who was one of the very few women to be an accepted member of the impressionist circle in the late 19th century. By her mid-twenties, Morisot, a beauty with dark hair and gleaming eyes, had been proposed to a number of times by various suitors, but she declined each of them in favor of pursuing art, she said, over domestic cares. Luckily, she had familial means and support to study under some of the great painters of the time, including Camille Corot, and had been presented widely and approvingly throughout Paris.

In 1867, though, the young Morisot’s life took a turn after a chance meeting at the Louvre Museum. While she was sketching from one of the Louvre’s masterpieces, she was introduced to Edouard Manet, a painter who was both modern and traditional, conservative and yet quite scandalous, and who was famous--or infamous, really-- for his outrageous paintings like his Olympia and Luncheon on the Grass. Both artists had much in common, with similar familial backgrounds, and they traversed in similar artistic circles, with both of them having been selected for the prestigious annual art exhibition, the Salon, in Paris. Immediately, the artists developed a kinship, a mutual respect, and a need to work together in paint and pigment.

According to some historians, it seems that the relationship began with Berthe in the position of muse. Edouard Manet painted 12 separate portraits of her- and it should be noted that there was nothing improper that was occurring during Morisot’s modeling sessions. Morisot was always properly clothed, and her mother, as custom for unmarried women entailed, accompanied her as her chaperone. But the fact of the matter remains that Manet painted Berthe Morisot more than any other woman, including his own wife. And there’s something about her in these images, too-- deeper, more brooding, a bit more mysterious than nearly any other woman depicted by an impressionist or post impressionist. Perhaps it is because there is a sense of longing there-- for what remains up for debate. But as viewers, we can intuit that she isn't necessarily happy in the position as model and muse. No-- in fact, she was probably much more comfortable standing behind the canvas than in front of it. That way, she could be the one in control of the situation.

And control was probably something that she would have wanted a bit more of, considering that she probably felt a little unmoored in terms of her romantic interests. The truth of the matter is that in her surviving letters, Berthe expressed that she had strong feelings for Manet, but that those feelings were complicated by frustration and jealousies. Her letters, by the way, were compiled and published by her grandson, so there is no way to tell how heavily they were edited and what may or may not have been removed, in terms of revealing Berthe’s private life. What is clear, though, is that she went through a profound period of self-doubt, as many creators do, and certainly seeing her friend and ally succeed may have been difficult at times. That, combined with the possibility that Berthe may have felt an unrequited love for the artist, certainly complicated their relationship. So it may have been an embarrassment and a disappointment, but also somewhat of a relief, when Manet suggested that she marry his younger brother, Eugene. And she said yes.

The incredible thing about Berthe Morisot, though, is that even after her marriage and after she became a mother to her only child, Julie, she continued to pursue her artistic career-- a rarity, to be sure, in the 19th century. And she and Edouard Manet continued their professional relationship throughout, even if it lacked the same intensity than prior to her marriage to his brother. They gave each other advice and helped each other experiment-- he was known to have dabbed and cleaned up parts of her paintings (with her permission, mostly), and she encouraged him to loosen up his brushwork and lighten his palette, following in her much more expressive and impressionistic style. But this new period in Morisot’s life also marked the end of the portraits that Edouard Manet painted of her. And interestingly enough, Berthe Morisot never, ever, painted him-- not even prior to her marriage. That artist slash muse relationship was only a one-way street.

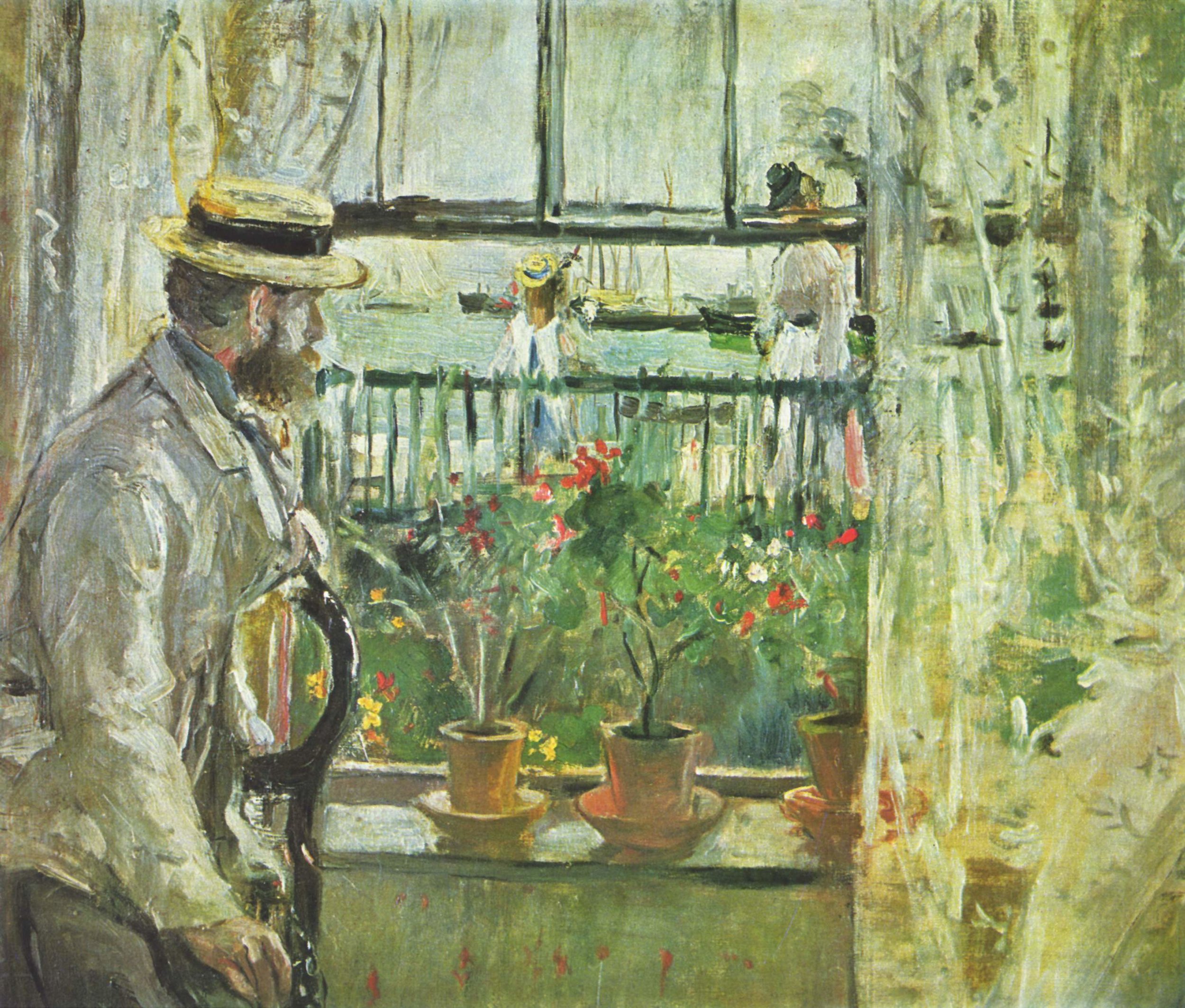

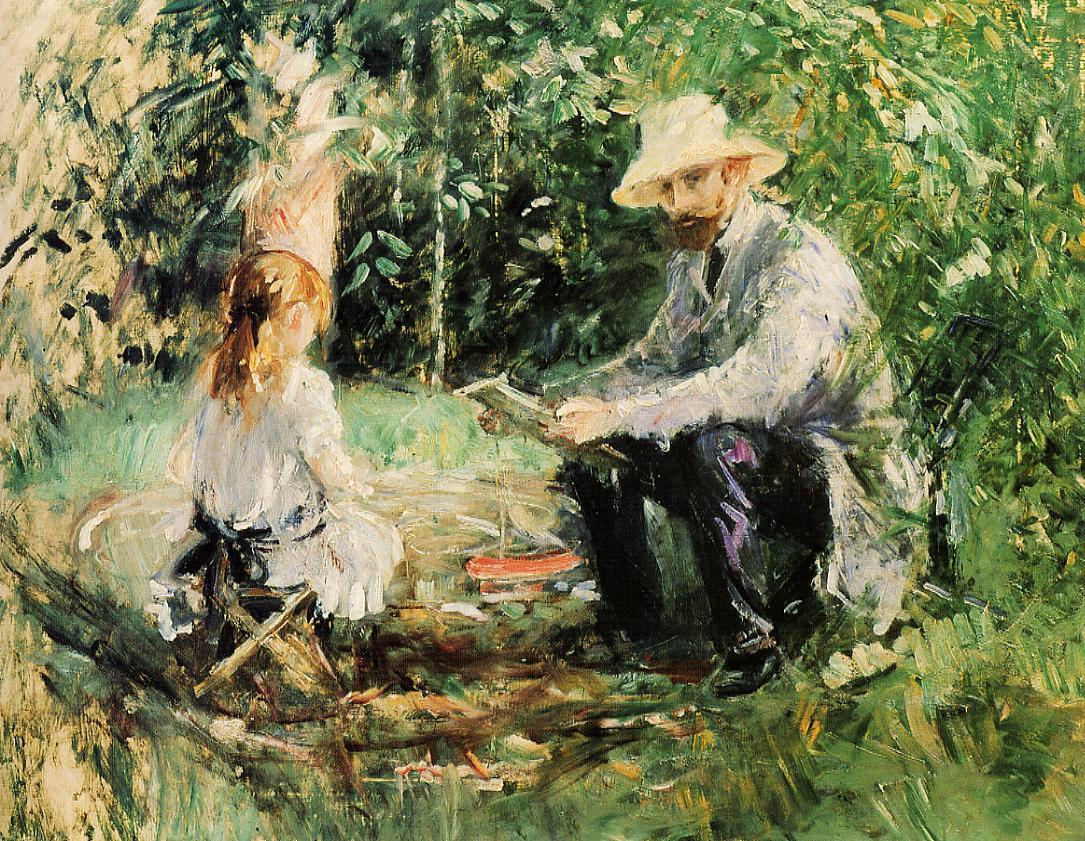

Perhaps Berthe Morisot didn’t want to paint Manet for any number of reasons. Maybe the intensity of her feelings for him--whether they be platonic or romantic-- were just too much for her to work out on canvas. Or maybe she simply wasn't interested in Edouard as a model. But there could also be a third reason behind her disinterest-- she already had another muse: her new husband. By all accounts, there was a true and real love between Berthe and Eugene, who was very supportive of his wife’s artistic career. Sure, it helped that he had a brother who was also extremely successful in the arts, so he was probably already inclined to be knowledgeable and helpful in this arena. Regardless, Eugene was the perfect match for a woman who strongly wanted to carry on in her own independent work and study. And this unrestricted support paid off visually, as Eugene became a frequent model for his wife-- sometimes portrayed by himself, and sometimes shown in the company of their daughter-- who herself was another of Morisot’s most favorite subjects. Eugene posed for his wife occasionally until his death, in 1892, at age 58. Morisot herself died only three years later, in 1895, at age 54.

So, when we get right down to it, who, really, was Berthe Morisot’s muse? In essence, the connection between her and the Manet brothers might be able to fulfill both sides of the muse and artist relationship that we discussed earlier in the episode. The romantic slash sexual side--the one so favored by Picasso and others-- could be satisfied by the inspiration that Morisot received from her husband, Eugene. But the mental connection stipulated by Germaine Greer as the much more important factor in the Muse and artist relationship-- well, that one could have been Edouard Manet. So, which one, then, was her true muse? Or did she have both as her muses at the same time? Indeed, the concept of the muse in today’s sight is so old-fashioned and limited. Maybe neither man could or should be considered Berthe Morisot's Muse. Claiming someone as a muse can put a little too much power into the hands of the non-creator, you may say. So instead, perhaps we can just accept that Morisot was a great artist who found inspiration in various people in her life, regardless of their gender and her relationship to them. Really, what’s love got to do with it?

Thank you for listening to this episode of the ArtCurious Podcast, a proud member of the Modest Podcast Network. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal. Production assistance for the show is provided by Kaboonki Creative. K-A-B-Double O-N-K-I dot com. For images, information, and links to our previous episodes, please visit our website at artcuriouspodcast.com. You can also find us on Facebook, and we’re posting on Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod. If you like this show, please consider donating to help offset the costs associated with keeping it going, and thanks to all of you who have already donated. Don’t forget, too, that if you don’t have any change to spare that you can support us just as importantly by leaving a review and rating on iTunes. It’s the number one way to help us find new listeners. Please check back with us in two weeks, as we continue to explore the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in art history.